Artificial intelligence is set to unleash an explosion of new technologies and discoveries into the world. This could lead to incredible advances in human flourishing, if we do it well. The problem? We’re not very good at predicting and responding to the harms of new technologies, especially when those harms are slow-moving and invisible.

Today on the show we explore this fundamental problem with Rob Bilott, an environmental lawyer who has spent nearly three decades battling chemical giants over PFAS—"forever chemicals" now found in our water, soil, and blood. These chemicals helped build the modern economy, but they’ve also been shown to cause serious health problems.

Rob’s story, and the story of PFAS is a cautionary tale of why we need to align technological innovation with safety, and mitigate irreversible harms before they become permanent. We only have one chance to get it right before AI becomes irreversibly entangled in our society.

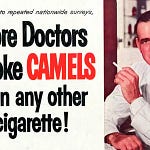

Tristan Harris: Hey everyone, it's Tristan. And last episode we had the historian Naomi Oreskes on to talk about the playbook that various industries from big tobacco to pesticides to fossil fuels have used to delay a reckoning with the harms of their products.

Now, to really understand that playbook and to help build our defenses against it, we wanted to have someone on the show whose had that playbook thrown at them and yet triumphed against it.

Rob Bilott is an environmental lawyer who spent nearly three decades taking on the makers of forever chemicals or PFAS. Now, these were chemicals that were first mass-produced in the 1950s, and they helped build the modern economy. They've been used in everything from dental floss to food packaging to airplanes, to Teflon non-stick cookware. But they were also poisoning us. PFAS had been shown to cause a whole range of health problems from cancer and diabetes and even fertility issues. And they're called forever chemicals because they persist in the ecosystem in our environment and our bodies indefinitely.

They're in the blood of nearly everyone in America, including you and me. They're in our water, they're in our soil. And the thing is, the big companies that were making PFAS, DuPont and 3M, knew about the harmful side effects and yet kept that information hidden. A ProPublica investigation found that between 1951 and the year 2000, 3M produced 100 million pounds of the chemicals, roughly the weight of the Titanic. And most of that came after they knew the chemicals were toxic.

So you'll hear me make a lot of comparisons between today's AI rollout and the story of PFAS, but it's really a cautionary tale about what can go wrong when we move too quickly and too excitedly to deploy a new technology without a deep understanding of the negative externalities and how it'll affect the environment. Now, AI is set to exponentially increase the pace of all new technology and all new science. So whatever misalignment led to these forever chemicals needs to be fixed right now before we put a booster rocket on our technological process. Now, this was a fantastic conversation and I hope you gain valuable insights from it.

Rob, thank you so much for coming on Your Undivided Attention.

Rob Bilott: Oh, thank you. Thanks for having me. Pleasure to be here.

Tristan Harris: So Rob, let's just give a little bit of a background on you. So you wrote a book that I highly recommend called Exposure, which they made a movie about in 2019 called Dark Waters, which I also highly recommend. Mark Ruffalo playing you. And reading it I was actually surprised to learn that you started this work as an environmental lawyer, but on the corporate side. So for our listeners who haven't read the book, how did your journey with PFAS start?

Rob Bilott: Sure, yeah. I'm actually still working at the same law firm almost 35 years later, but I started my legal career back in 1990 with the law firm of Taft Stettinius & Hollister in Cincinnati, Ohio. And when I joined the law firm back then, really had no idea what environmental law was, what environmental lawyers did. Nobody in my family had really been a lawyer before.

So when I joined the firm in 1990, I really began learning that process and what it meant to work as an environmental lawyer. And a lot of the folks that I was dealing with at the time that the law firm was representing back then were primarily big companies, a lot of big corporations, a lot of big chemical companies. So for the first eight years or so of my career, I was really working with those folks, trying to help them navigate the environmental law world.

And what I learned was we had this incredibly complex system that had been created in our country, federal laws, rules, regulations, state laws, rules and regulations, international treaties, local ordinances, this massive system that had been put in place to regulate and control what could go into the air, what can go into the water, what you can put into the soil. And really, after doing that for about eight years thought my career path was pretty clear. I was becoming a partner at the law firm, working with these corporate clients, but my career took a different path after about eight years in.

Tristan Harris: So how did it take a different path? As a lawyer and making your way up the firm, I'm sure there was incentives to keep doing what you were doing, but you took this very bold step in basically joining the other side in a way. What happened? How did you first get into discovering forever chemicals for listeners who are not aware of them?

Rob Bilott: It was a little bit of a roundabout process. I was in my office one day, the phone rang, and on the other end of the line, there was this gentleman that was rattling on in kind of an angry tone about cows dying on his property and that I needed to help him. And it was telling me all these details about what was happening on his property, and I was about to hang the phone up when he blurted out, "Your grandmother said you'd help." And so I paused a bit at that point and tried to figure out, "What's the connection here? How does he know my grandmother and why is he calling me?"

And what I came to understand was he was calling from Parkersburg, West Virginia, which was a town I knew well. My mom had grown up in Parkersburg, her entire family was there, so family holidays, birthdays, that's where we went. So when I heard that connection, I thought, "Okay, I'll at least listen, particularly if somehow he talked to my grandmother or knew her, I'll see if I can help him."

During that call, what we found out was this gentleman whose name was Wilbur Tennant was raising cattle on a farm outside of Parkersburg, West Virginia and calling because his animals had been getting sick. And by the time he called me, this was October of 1998, he had lost over 100 of these animals, had started dropping dead, and he was convinced he knew why. Right next to his property was a landfill owned by one of the world's biggest chemical companies, DuPont Chemical. And he had seen white foam coming out of the pipe, coming out of that landfill going into the creek that ran through his property and he was convinced there was something in that white foam that was making these animals sick, but nobody would help him.

He had called the state EPA, he had called the Federal Environmental Protection Agency. He had called DuPont. Nobody was giving him clear answers. So apparently he was complaining to his neighbor one day who had been on the phone with my grandmother. They were friends. And she had said, "Hey, my grandson's an environmental lawyer, he can help you." So I'm hearing this story and I'm hearing that this is something apparently happening in what I viewed as my hometown. And it involved a landfill, and it was a landfill that had a permit by one of these big chemical companies, DuPont.

Now, we represented a lot of those big companies, but not DuPont. DuPont was not one of our clients, but I knew them well. I was familiar with them. I knew they had great lawyers, they had great scientists. So something, if it was this obvious and DuPont was involved, we could probably help Mr. Tennant get to the bottom of this pretty quickly. So based on that phone call, I invited him up. He came to our offices. And we eventually decided we'd see if we could help him.

Tristan Harris: And how did he know? What were the symptoms that these cows were developing? He said 100 cows dropped dead, but I know that there was a bunch of really gruesome evidence of this.

Rob Bilott: Yeah, there was. And we had invited Mr. Tennant to come on up to our offices and bring with him what he had. He told us he had a lot of evidence and a lot of proof of what was happening. So when he came up, he and his wife came armed with boxes of videotapes. These were the days of VHS tapes. So he came armed with these VHS tapes and photographs, and we spent hours looking through those tapes and those photographs and what we saw was pretty compelling.

There was video. Mr. Tennant had started taking video as far back as around 1995 of what was happening to these cows. And you could see they were wasting away. They were like skin and bones. No matter how much he would feed him, they kept losing weight. You could see tumors on the animals, you could see the fur on their hoofs were being eaten off by something in the water. Their teeth were turning black.

After these animals had started dropping dead, Mr. Tennant himself actually started cutting into the animals and then videotaping what he was seeing. So we had video and those that may have seen the films, Dark Waters or the documentary, The Devil We Know, you see this video, it's the actual video that Mr. Tennant took of the deformed organs and the green ooze. So pretty compelling stuff, plus video of this white foam coming through the creek that these animals were drinking. And even more compelling, you would see these calves that had been born either stillborn or with birth effects, their eyes were cloudy. So pretty compelling stuff.

Tristan Harris: And then what happened next? How did this case proceed?

Rob Bilott: Well, after reviewing all that and seeing there was something obviously in this white foam that was making these animals sick, I felt like this is the kind of thing I should be able to help this gentleman with because after all, I helped companies like DuPont get permits to run landfills like this. So I knew that there would be something from the government agencies identifying what types of chemicals would be allowed in the water coming out of that landfill.

And likely if there was some chemical causing a problem here, there would probably be monthly reports that were going in showing what the levels of those chemicals were. And with DuPont on the other side, they understood these rules, they understood the law. They had great scientists, something this obvious, we should be able to help pretty quick. So we agreed to take this case on for Mr. Tennant and his family. We're still litigating these issues over 25 years later.

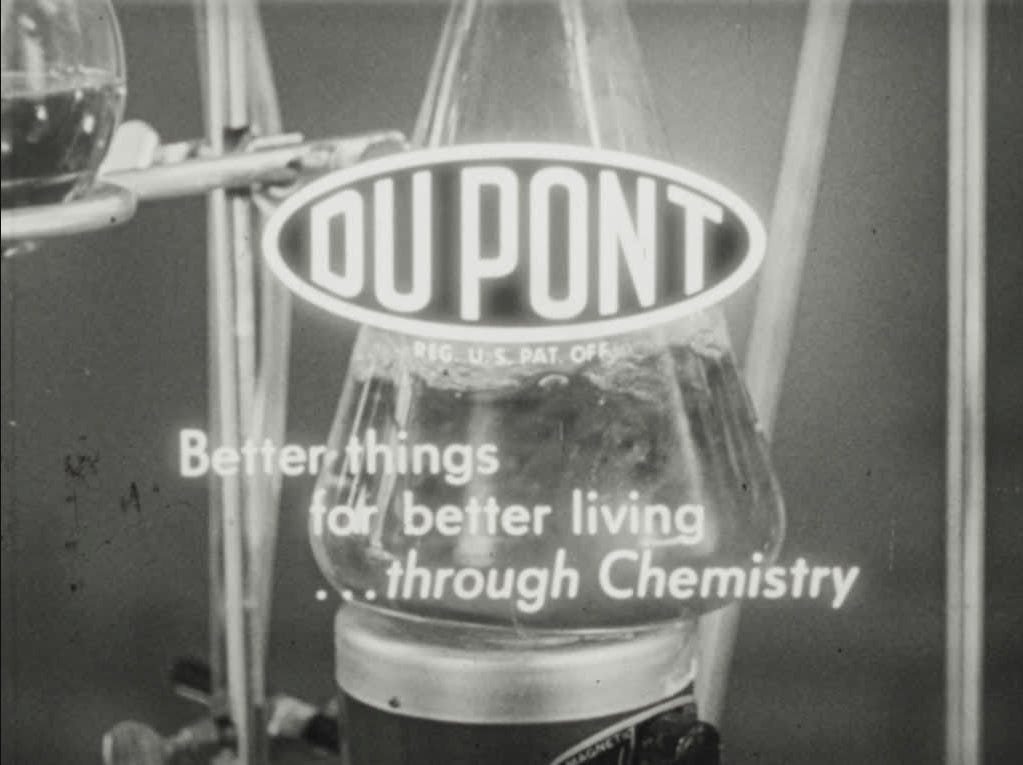

Tristan Harris: Before we get deeper into the harms and the toxicity here, we on this podcast talk a lot about the development of technology and how do we create a responsible innovation environment and just sort of steelman for a second. Let's talk briefly about the excitement of chemistry. DuPont had the motto, "Better Living Through Chemistry." Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate is asked, he's graduating in that famous film, "What industry should I go into?"

Rob Bilott: Plastics.

Tristan Harris: Plastics. So there is this sort of revolution where we as a species learn to speak the language of nature, of chemistry and actually get to basically invent new forms, new chemical bonds that we never invented before. Can you just talk a little about what was this excitement? What were the kinds of products? What were the techno-optimist views of the time?

Rob Bilott: I think that's a critically important aspect to really understand when you're talking about the whole forever chemicals story and how did this happen? Why did it happen? Why did it continue happening as long as it did? You really have to look at the timing of when all this happened. You're talking about chemicals, these forever chemicals that were invented around the time of World War II, really kind of an outgrowth of the Manhattan Project and chemicals that started getting put out into the world in the early 1950s. The US Environmental Protection Agency didn't come into existence until 1970 after Silent Spring and Earth Day and all of that occurred later on. So then all of these federal laws and rules governing what could go into the air and the water came after that in the late '70s.

Tristan Harris: So there was 20 years of essentially this new domain opening up, this new sort of technologically enabled domain and we're pumping out new kinds of bonds, new kinds of products, and we thought that we were doing good. Let's talk about the benefits. What were the kinds of adhesives and benefits that these chemicals were providing?

Rob Bilott: Absolutely. You go back and look at that period of time when this outgrowth of this Manhattan Project, they came up with this new way of making materials that had never existed on the planet before. They were able to connect carbons to fluorine in a way that made this whole new class of chemistry, these perfluorinated materials. The 3M company in Minnesota really pioneered this way of connecting carbons to fluorine and creating these fluorinated organics that had never been on the planet.

And they even started advertising, 3M did, in the early 1950s, putting ads in magazines, asking people to give them ideas of how these new chemicals can be used, what kinds of products might we be able to use these in? And around the same time, this is all going on with 3M, DuPont has created this new material called Teflon, also sort of an outgrowth of that same Manhattan Project research.

DuPont is having a hard time really finding a way to make this material and keep it really stable. And so they're looking for a chemical to use in making Teflon that will help them in that process and help them bring Teflon into additional products and things like cookware and other uses. They find this chemical that 3M's making, one of these perfluorinated organics, and they start using that in early 1951 to make this Teflon process.

So you've got these companies that are out there actively trying to find, "How can we put these materials into these new products, bring them out into the world?" And again, it's before these federal agencies and rules and laws existed about what can go into the world and the air and the water. But those companies had their own scientists that were researching this and trying to understand what will these chemicals do when they get out into the world?

Tristan Harris: So these scientists were actually starting from the beginning to discover the effects, like they were doing safety testing?

Rob Bilott: Absolutely. DuPont had started purchasing one of these chemicals from 3M, and they called it PFOA, perfluorooctanoic acid. It had eight carbons attached to a fluorine. DuPont was buying that PFOA from 3M to use in making Teflon. They started buying that by 1951. So they started shipping massive quantities down to West Virginia where they were going to use it in making Teflon at this massive plant along the Ohio River.

Well, DuPont's starting to think about launching Teflon into the world, putting it onto pots and pans. It's just going to go out all over the place in 1962. So they have all of their internal scientists where they've got a massive laboratory in Delaware where they've got some of the world's best scientists. And they're looking at this saying, "Wait a minute. This stuff's about to go out into the world. It's got this really unique man-made chemical structure. It's really strong. It's not going to break apart. What's it going to do to living things when it gets out there?"

Tristan Harris: So they at least did have that question then that they-

Rob Bilott: Absolutely.

Tristan Harris: ... they suspected because this was a new chemical that was man-made that had never before existed on planet Earth, "We don't suspect that it's just going to degrade in the environment like other kinds of products."

Rob Bilott: Right. They understood that because of that really strong chemical bond, those carbons to fluorine, it was not going to break apart. And so the concern was what's it going to do to living things? It's going to get out there, it's going to stay in the soil, it's going to stay in the water. What about living things? So that's when they started doing their own internal studies on animals, rats, mice, rabbits, guinea pigs, dogs, monkeys.

They were doing their own studies again, even before EPA existed and finding this stuff's incredibly toxic. So not only will it get out and stay in the environment, it can cause all kinds of toxic effects. And one of the things that really set alarm bells off was... This was by the 1970s. It's the time period where people are starting to put fluoride in drinking water for cavities. And so some researchers had gone out trying to figure out, "Hey, is that kind of fluoride getting into people's blood?"

And so they had gone out and collected samples from US blood banks in 1975 looking for that type of fluoride that they were purposely putting in the water. And yes, they found that was getting into people's blood, but those researchers found a different type of fluoride that they weren't expecting, this organic fluoride. And when they went back to the research, they saw this doesn't exist naturally. Where's it coming from? And so they had identified 3M. "Hey, 3M's making this stuff. I wonder if it's theirs?" And they had gone to 3M and asked them, "Hey, is this your chemical that we're finding in the general US population's blood?"

Tristan Harris: Because this is not the population that lives just downstream from the plant that's making it.

Rob Bilott: Correct.

Tristan Harris: This is the general population.

Rob Bilott: These are blood banks across the country that they had collected blood samples from. So they had gone to 3M. Keep in mind the timing here, this is as early as 1975 and said, "We're finding these unique, organic fluorines in the general population's blood. Is it your stuff?" 3M, we know from later documents through litigation, said they pled ignorance, but internally confirmed it was theirs.

And so they started then testing their own workers and seeing, "Oh, it's building up in our workers' blood." They tell DuPont who's buying this stuff for Teflon and they find DuPont workers are getting it in their blood too. So it was at that point the companies were now concerned, not only is this stuff going to stay in the environment, it's toxic to animals. What's it do to people if it stays in their blood for long periods of time? Because it's like a ticking time bomb. So that's when they start cancer studies, long-term cancer studies, and by the '80s, they've confirmed it can cause cancer.

So you've got all of these internal studies going on for decades within the companies, and it's all coming out bad. But in the meantime, those chemicals have been found to be useful in not just Teflon, but a huge variety of different products being used all over the economy.

Anything that's stain resistant, waterproof, grease resistant, so fast food wrappers and packaging, clothing, carpeting, cosmetics, and then eventually firefighting foams start using this stuff as well. So by the 80s, by the time they're finding this stuff can cause cancer in the animals, sales are booming of these chemicals. They're being used in all these products. So you have this real problem of, "What do we do? Because we found out this is bad stuff, yet they're incredibly profitable."

Tristan Harris: I think so much of what we cover on this podcast and what we think about in our work at Center for Humane Technology is inconvenient truths. You release a product with good faith, you think that this is going to help people. And what you were saying earlier about Teflon, and we discovered this chemical, we want to ask people, "What should we do with it? What should we do with this powerful new water-resistant, stain-resistant protective chemistry?" And it makes me think about the AI companies that are releasing these AI systems and saying, "You tell us what we can do with it. Try to use it for everything. And let's see what it can be used for."

Now, AI itself is not toxic in its own right but I think the pattern is very similar. You have a wild west of a new technological domain. We open up the domain of chemistry, we don't know what to do with it. We want to see, so we open up the innovation frontier, we let people experiment, try all these different products. And then you realize later on that after sales are booming, there's a problem. But by the time you realize there's a problem, there's too many incentives, there's too much entanglement. Too much of our profits are dependent on the problem, whether that was fossil fuels or social media booming business models pumping out human attention even at the cost of unraveling democracies. I'd love to hear more about how this story progressed. How do you go against these incentives? How did your case with... Who was it again? The cattle farmer?

By the time you realize there's a problem, there's too many incentives, there's too much entanglement. Too much of our profits are dependent on the problem, whether that was fossil fuels or social media booming business models pumping out human attention even at the cost of unraveling democracies.

Rob Bilott: Mr. Tennant, Wilbur Tennant and his family.

Tristan Harris: How did it continue with Mr. Tennant?

Rob Bilott: Yeah. Well, when we first brought the case for Mr. Tennant, again, we thought it was going to be something fairly simple. It was going to be something regulated by the permits. And when we started bringing the case and moving forward against DuPont, we started getting access to DuPont's internal documents. It wasn't easy. We had to go to court many times and get orders to force a lot of these documents to be turned over.

But eventually, as I started weeding through all of these internal files, what I saw was we had this PFOA chemical that 3M had invented, was selling to DuPont to make Teflon. And I'm seeing all of these internal records indicating its incredibly toxic, persistent. It was causing cancer in the animal studies in the '80s. And then what we saw that was the most disturbing was that massive quantities of that stuff apparently had been dumped into the landfill that Mr. Tennant was complaining about.

And we also found out what does this stuff do when it rains or it hits water? It creates white foam. And so what we had understood had happened here is by the '80s when DuPont was finding out this chemical that they were using to make Teflon was toxic, persistent, bioaccumulative, could cause cancer, they were concerned about, "Well, wait a minute. We're emitting this into the air from our factory. We're putting it directly into the Ohio River. We're dumping these sludges from the factory into unlined pits all over the property. What if it's gotten out into the water supply?"

So they had gone out and actually sampled and found, yes, the chemical was in the public's drinking water. And then they were trying to figure out, "Well, how do we make this go away?" So they had actually dug up thousands of tons of this stuff, this sludge from the factory and had taken it and dumped it into the landfill next to Mr. Tennant's property in the 80s. And that's what we understood was causing the problem with the cows.

And when we figured all that out, we were able to settle the case for Mr. Tennant. But what we had also figured out was this now was a much bigger problem than just Mr. Tennant and his cows because what we also saw in those documents was this chemical that was in the landfill, in this foam and causing the problems in the creek, that same chemical had been found in the entire community's drinking water that DuPont had gone out and sampled and had found that as early as 1984 in everybody's drinking water, but hadn't told anybody.

And we were really concerned that thousands, tens of thousands of people might've been exposed to this. We had just been talking about the fact that, gosh, all this was occurring before there was a US EPA, before these rules and regulations came into play. Well, by the 1980s, there was a US EPA. There were statutes, rules and regulations governing what kind of chemicals could go into the air in the water.

So I was trying to figure out how was this happening? How was this possible? Why weren't there regulations about what was in the water and what was going on there? And what I saw really opened my eyes to a much bigger problem with the entire US regulatory system in the way in which our rules and regulations about chemicals in the environment involved. Because what I saw there is, yeah, when the EPA came into existence in 1970 and they started adopting these rules to regulate chemicals going into the environment, they really focused on new chemicals from that point forward, from the late '70s on. For the existing chemicals like the ones-

Tristan Harris: They were grandfathered in.

Rob Bilott: Right. Like the ones 3M and DuPont had been making since the '50s. Those really had been grandfathered in. And the law essentially said it was up to the companies themselves making or using those to alert the EPA if there was some substantial risk to the human health and the environment from those chemicals. In other words, the law left it up to the companies to report whether there was a problem.

Tristan Harris: Which of course they're never going to do on their own.

Rob Bilott: Right. It really opened my eyes to the fact that what happens when a company doesn't report? Because what I was seeing was there was tons of information available to both 3M and DuPont saying this stuff was bad. It was causing all kinds of problems in animals, possibly workers as well. It was getting into public water. It was being found in the general population's blood. But nobody had been told because both companies had consciously decided not to tell.

Tristan Harris: Really just take a moment to take all this in. I remember when I first learned about forever chemicals, and it's just devastating when you realize just that we are all living with it all and that this got out there and how irreversible the damage is. And I think it's one thing when a corporation makes a technology product that offers a lot of benefit and has some negative externalities. We didn't know that at the time. We realize it later and then we remediate it. What's difficult about forever chemicals is how permanent and forever the impacts are. And I think where there is a permanent or forever impact, we have to have a more precautionary sort of approach. What I want to ask next is Naomi Oreskes, we had on this podcast who's the author of the book, Merchants of Doubt. I wanted you to talk a little bit about how science played into this... I think it was called the Cattle Study or the Cattle Committee. That was... Was it DuPont that started up?

Rob Bilott: Well, that was another pretty interesting educational process for me. When I started into this and started my legal career, my perception of science was science is science. There's the facts and the truth. And if a scientific process or scientific study is done, the results, whatever they may be, end up published and everybody can rely on that and the science moves forward. And what I saw with the story of forever chemicals really changed my entire perception of that.

Because what I saw was science being manipulated and the ability to control what actually gets published and makes its way into the peer review, what the public and the regulators actually see about the science. And it really started with, as you mentioned, this Cattle Team that was created when Mr. Tennant first started complaining that something was making his cows sick. And we were just starting to bring litigation against DuPont back in 1999 to address all this.

The first response we got from DuPont was, "Oh, no, no, no. No need to do all of that. We don't need to fight in court. We're going to actually put together a panel of some of the world's best scientists, three from DuPont, three from US EPA that are going to study what's happening to these cows and they're going to tell us what's really causing the problem here." And at the time, I thought this was great. This was the top agency in the country, the US EPA and one of the best chemical companies on the planet with some of the best scientists.

Tristan Harris: So at the time you thought this was actually a good idea the way that they were constructing-

Rob Bilott: I did.

Tristan Harris: ... they had the top three scientists from the EPA, the top three scientists from DuPont. So we've got a neutral or sort of semi-neutral committee and that you would trust that impact. At the time you weren't skeptical of that?

Rob Bilott: Absolutely. I was not. And so when I got their report though, and the report essentially said, "We can't find any chemical issue here, and if anything, it looks like maybe the family itself just doesn't know how to raise cattle or maybe they're even abusing these animals." Now, that really set red flags off for me and made me start to question my whole perception of that process because I had been to the farm. I had seen the way these animals were treated by the family. These folks knew how to raise cattle. They were not abusing these animals. So I really became suspicious of what was going on here.

And what we came to learn was the entire process was essentially corrupt. That DuPont had set this up to derail and sidetrack EPA because the US EPA had actually come out in response to Mr. Tennant complaining back in 1997. They had started an investigation. And that was about the time we started bringing our lawsuit. Well DuPont, to stop that investigation and to deflect that said, "No, no, we'll create this panel. Let's let the panel handle that."

Well, what we didn't realize were of the three scientists DuPont appointed, one of them had been studying PFOA for years, had been actually involved even in the first cancer study. Yet those scientists essentially never told the EPA folks that PFOA was in the water. They'd never even sampled the cows or the water for PFOA. So the whole process was set up and controlled by DuPont in a way to prevent the correct scientific conclusion from being reached. And then later after the Cattle Team fiasco, what I started to see in the internal documents were all kinds of studies that were being done, not only of other animals, the rats, the monkeys, the rabbits, et cetera, but worker studies as well, lots of studies that were showing real concerns, toxic effects, possible cancer effects. Yet those results were not appearing in any of the published peer-reviewed literature.

And what we started to see was DuPont and 3M were carefully picking and choosing what actually got sent out for publication. They weren't publishing the stuff that they thought was harmful. Then what I saw was even the journals, as far as who was publishing, the companies were controlling a lot of that peer review process. DuPont and 3M were carefully making sure that their folks were the ones publishing about the chemical. So essentially, anytime anybody tried to publish something new on it, it was the DuPont and 3M folks that were reviewing the paper.

Tristan Harris: It's like jury selection. You just manipulate who's on the jury.

Rob Bilott: Exactly. And so if they were finding there was a problem, it was being rejected as junk science. So we were seeing a complete control and manipulation of the science by these companies. So about the time I was finally figuring all this out in the early 2000s, all of the scientific peer reviewed literature had been so carefully manipulated that if you were to try to walk into a court and say, "Here's the current science," it was all going to support DuPont and 3M.

Tristan Harris: And this is a common strategy of companies where, yes, you can do science, but you cherry-pick which data you're sourcing from so that the study has the result that you want. From our experience with Meta or Facebook, they did a study asking does it affect the mental health of young people? And when they handed that study and the data sets to a bunch of researchers, they counted basically with Facebook, there's the main product, the scrollable feed, that kind of facebook.com interface. Then there's the messenger product of people who are just chatting. And obviously people use the messenger product all day long, and then they sometimes go to Facebook and they sort of distorted the data to count usage that included everybody who just used the Messenger product once a day in their data sets. So basically most of the psychological harm from Facebook comes from the actual product itself, the main Facebook page.

But they were counting all this extra data to dilute the effects so that it wouldn't show up in the data. And this has happened all the time. We've interviewed Francis Haugen, the Facebook whistleblower, yet another example where companies know harm. They did the research. And one of the structural problems we have to deal with is that there's an asymmetry between what the companies will know and what the external bodies that are supposed to regulate them could know. And part of that has to do with technical understanding. I'm sure there was new technical scientific frontiers that are known inside of DuPont and 3M that maybe the EPA doesn't know about and how do we deal with that structural problem?

Rob Bilott: Yeah, absolutely. It's one of the reasons I wrote the book Exposure. Because the problem is what we see throughout the way the system is set up, the agencies and the public is at an incredible disadvantage because what we saw here is the companies making this stuff and doing the studies and generating the science that was showing incredible harm and risk to human health and the environment. They were essentially controlling how of that information made its way out to the public, to regulators, to the scientific community.

You mentioned Merchants of Doubt, manufacturing doubt. The companies here use the same consulting firms that you saw in tobacco and other instances where the companies wanted to make sure that they completely controlled what people understood about the chemistry and the risks of these chemicals. And they employed these consultants that would make themselves available to the press or to regulators or to lawmakers, to the public to tell them, "There's no evidence these chemicals cause harm. Anybody that suggests otherwise is a junk scientist and we need much more data and science before anything can be done to regulate these materials."

That went on for decades. I saw documents I never thought I would see actually written down where consulting firms are actually laying out the game plan of how to manipulate the process that way, how to control the science, how to make sure lawmakers only get certain talking points and messages.

Tristan Harris: So you saw the strategy documents that came out in discovery through the case?

Rob Bilott: Absolutely. And it's just remarkable. It's very frustrating to see that and to see, "Wait a minute, this is the way this really happens here." And it was incredibly effective.

The way the system is set up, the agencies and the public is at an incredible disadvantage because what we saw here is the companies making this stuff and doing the studies and generating the science that was showing incredible harm and risk to human health and the environment. They were essentially controlling how of that information made its way out to the public, to regulators, to the scientific community.

Tristan Harris: I'm just curious at a human level, here we are. There are scientists that discover this is causing cancers in animals and people discovering in the blood of their own employees. You would think as just a regular conscious, compassionate human that the people inside the company would try to do something to stop this. And I think people listening might say, "Gosh, they're not doing anything. They just sound so sociopathic." And could you just explain... I'm sure you've interacted with people inside the company, people who are aware of these things. Did you meet caring people who tried to do something, who tried to raise the alarm, and what response did they get?

Rob Bilott: I think there was such an incredibly complex number of factors that created this sort of perfect storm that allowed this to happen. You did have folks within the companies who were doing good science and saying, "We need to say something about this," or, "This looks pretty toxic," or, "This seems to have caused cancer." You even had the lawyers within the company trying to alert the client, the company, "Hey, we probably need to do something about this."

Unfortunately, a lot of that got squelched within the company. You had incredibly profitable product lines that were at risk. We're talking about billions on an annual basis if you start looking at all the different products that these PFAS forever chemicals were in. And if you started asking folks within the company, "Well, hey, you saw this information, why didn't you do something?" Or, "Why didn't you say something?" So often the response was, "Well, that wasn't my job. I thought somebody else was responsible." People trying to deflect this off themselves to think, "Well, I wasn't the one who made that decision. Somebody else did."

Tristan Harris: And so after these problems were discovered, many listeners might be asking, "So why didn't 3M and DuPont immediately start working on alternatives that would be safe?" And did they do that and they were just more expensive? Talk about the way that these products have evolved over time. How many PFAS chemicals are there? How did they try to respond and come up with safer products?

Rob Bilott: Yeah, I think when the warning flags first started going off internally within the companies in the '70s when they found out the stuff was getting into human blood, you did see in the company start to internally look for alternatives, was trying to figure out whether we could switch to something else. And ironically enough, a lot of times the decision came back to, "Well, we're not required to switch to something else and it's cheaper to keep on using this. We'd lose a lot of money if we switched to this or the other thing."

And of course, the irony was the only reason it wasn't regulated was because the agencies didn't even know it existed because the companies had not told them. But nevertheless, we see the internal discussions about whether to switch and the economic evaluations of whether to do it or not. And you see finally, 3M, the original inventor of these chemicals, decide to pull two of the most profitable ones off the market back in the year 2000. PFOA, which is the one they were selling to DuPont for Teflon and PFOS, which had been used in Scotchgard and firefighting foams because suddenly the regulatory agencies were starting to raise questions about it, customers were starting to raise questions. So 3M decides to pull those off the market.

Unfortunately, DuPont who also could have switched away from PFOA to something else at that point makes a business decision, "Hey, we can take over that market." So they actually made the decision to begin making their own PFOA. Now, as that story has finally made its way out and the world is finally hearing how bad these chemicals are, we're now realizing PFOA and PFOS, the ones 3M phased out, and DuPont eventually also phased out, those were just two within this family that we now call PFOS per and polyfluoroalkylated substances.

There's an entire family of these man-made chemicals that have carbon and fluorine. There's not just two. There might be up to 14,000 of them. So as we learn about what was covered up and how bad these chemicals are, and we now know there's all these other chemicals, now we're finally having regulators, the scientific community, the public, demanding that we move away from these and to take them out of products. So we just now had 3M, original inventor, agreed that it'll stop making the rest of these PFAS by the end of 2025. And other companies are now also committing to start switching away. And really what's driven that is the fact that the information has finally come out and consumers, armed with that information, are saying, "We don't want this in our products."

Tristan Harris: So one of the reasons I was so excited to have you on is that Demis Hassabis, who's the founder of DeepMind, the AI company, said, "If you solve intelligence, you can use intelligence to solve everything else." And what he means by that is that intelligence is the thing that brought us all of humanity's science, all of humanity's technology, all of humanity's military advancements. So if you can automate intelligence, you can basically automate infinite scientific, technological and military discoveries.

And so in a way, AI is going to exponentiate the existing imperfect process by which humanity develops new domains of technology. And so when I think about it's like we're about to set off a kind of Cambrian explosion of brand new technologies into the world through AI. And so what this forces us to look at and reckon with is is our current process of deploying technology misaligned in some way? And the examples of tobacco, asbestos, pesticides, forever chemicals, social media, show us pretty clearly that there is a imperfect and misaligned relationship.

And it has the same playbook every time. You build a product, you release it onto people, they're sort of guinea pigs. Maybe if you're lucky, there is internal research being done to actually test to see if there is some negative harms. If the harm show up, that harm is suppressed. There's a cover-up. There's PR consultants, there's fear, uncertainty, doubt. Then there's asymmetric power. They're making billions of dollars. They hire more lobbyists than there are members of Congress. And then you have the problem of corporate capture where the EPA has a revolving door and the only people... If you sort of steelman it, on the good side of it, the only people at the EPA who might know how to regulate these things are the ones with the technical understanding. So they're from the company. So you get people at the regulator who used to work at the leading executive class at these companies.

And we see that with all of these different domains of technology. And so I think as we think about AI, that's about to exponentiate the number of new technologies, we need to compress this playbook that you have been working so admirably for something like what, 26 years, it's taken for these lawsuits to come due?

Rob Bilott: Yeah. About 26 years.

Tristan Harris: And we still don't have justice, and this process obviously is imperfect. And so we need to compress that 26 years and just payouts and financial dues into a actual aligned relationship. We're deploying technology. We do the safety research early. We understand is this an irreversible harm or reversible harm? If it's irreversible, then we better do more regulation upfront and come up with a more adaptive process to do something about it. And I am just curious your reaction to that because I think that what you have observed and have so eloquently outlined and through the full structural process is this imperfect process by which good-hearted people get selected out. And the sort of sociopathic people who are willing to keep the machine going are the ones who get selected to keep staying doing the machine, who then justified under the logic of, "Well, that's above my pay grade. I'm just here to do my job." So as you think about that, I'm just curious your reaction, what are the lessons that we can learn for adapting our form of regulatory environments to meet this technological moment?

Rob Bilott: No, I think you've hit the nail on the head. I think that's an excellent point. And I think one of the reasons why it's important to also really focus on what's going on within our legal system, because we're not talking just about how science and technology evolve and agencies that are supposed to be regulating or dealing with it are capture or controlled. But what happens even when you figure out this is happening and you're trying to do something to either fix that, stop it, go back and address it. You're forced to go into the legal system. That's what we did with forever chemicals. So bring it into that world and getting it regulated and getting the laws changed was going to be incredibly time-consuming, incredibly difficult. And in fact, we're still working through that process, yet the laws are just now starting to change.

And the regulations, we just had the very first regulation on PFAS in the United States just a couple months ago after 26 years. So what we had to do... The only way to address it in the meantime was to move into the legal system, was to try to bring claims. And unfortunately, and again, this is one of the reasons I did the book, Exposure, was to talk about how that legal system is part of the problem.

Because the way it's set up, the person who's injured, the person who thinks they've been harmed by whatever this new science or new technology or new chemical is, they have the burden of proof when they walk into the courtroom, they're told, "You, you injured person. You have to come forward with sufficient experts, science, data to prove what you're saying, that this stuff is bad or harmful." Think about that. The average injured person doesn't have a scientific staff at their beckoning, doesn't have millions and millions of dollars and decades of years of worth of research to do it.

Tristan Harris: Can't do their own soil sampling and water sampling or sampling of their own blood. They're not going to do the citizen science.

Rob Bilott: You've got this almost impossible series of hurdles put in front of you. So as you try to move through that legal system, it is an incredibly difficult burden to overcome. Then we finally get to the point where we're able to prove that and what happens? The company simply tweak the chemicals a bit and call them something new and we're told, "Oh, you got to start all over again. All of these other chemicals, where's your proof on those?" So I think if anything, this story really highlights that you've got these major issues not only with how is the science controlled and manipulated, how are the lawmakers captured and controlled, but also the real problems with the way our legal system set up that make it almost impossible for folks to prove there's a problem with whatever this new thing is.

Tristan Harris: So I really want to hit on this because our legal system is good at dealing with... If you imagine a two by two of sort of short-term harms versus long-term harms and visible measurable harms versus long-term chronic cumulative and diffuse harms that are not attributable. So if there's an oil spill and Exxon causes the oil spill and we know where the oil spill was, and we know there was an Exxon tanker in Alaska that caused it, our legal system is pretty good at dealing with a harm like that.

But when you have this sort of invisibility of the externality, so in the case of shortening of attention spans is an invisible negative externality from social media, it's driving it. It doesn't do it all immediately. It's not one big jump. It's sort of over a 10-year, 20-year time period. And it's chronic. It sort of happens slowly. It's diffuse. It happens very subtly through the population. It's unattributable. Well, which company caused that shortening of attention spans? Which of these chemical companies are causing these cancers? How do we know that that liver cancer came from that forever chemical?

And so in general, I think one of the things that our legal system needs to upgrade itself into is dealing with these... We call it cumulative creep, instead of sort of these short-term discrete harms is cumulative creep. Climate change is like that. Forever chemicals is like that. Shortening attention spans is like that. I'm just curious, how do we have a regime that upfront requires and mandates more of the science, has a duty of care to basically focus on safety rather than just the profit? Because if you don't change that variable, even if it's harmful, their obligation is to switch to something else that keeps making money versus do the harder righter thing.

This story really highlights that you've got these major issues not only with how is the science controlled and manipulated, how are the lawmakers captured and controlled, but also the real problems with the way our legal system set up that make it almost impossible for folks to prove there's a problem with whatever this new thing is.

Rob Bilott: Yeah, again, you've hit on another very critical issue. What you constantly hear from the other side is, "Well, there's just not enough evidence. There's not enough proof that this is harmful yet. You need more, you need more. And let's just wait. Let's just wait until we get more data." Meanwhile, the harm continues. In the forever chemicals situation, it's decades.

And so in the forever chemicals world, what you saw was this countervailing called precautionary principle where folks would say, "Well, wait a minute. Why should you have to wait and actually prove that somebody has gotten cancer or somebody is actually deathly ill from exposure to this chemical before you can do something if you know based on the science that this stuff is harmful, could cause all of these potential harms, but it just hasn't happened yet? Do you have to wait until that actual harm has already happened and it's too late? Or do you act in a precautionary way? Do you do something to prevent the harm from occurring first?"

And that is the big conceptual debate we see playing out, particularly in the environmental world. You see much more of a precautionary approach, for example, taken in Europe where there's more emphasis on upfront studies and upfront data collection. But even in the US, we do have laws in place now that require testing and cancer studies on new chemicals before they come out. The problem is they don't necessarily get implemented that way. The companies cut deals with the EPA to let them go ahead and start making the chemical before they've done the study.

So even if the laws are on the book, it's the way they're implemented that's a real problem. And what's frustrating is if you go back and look at the history of what these companies knew and understood about this stuff decades ago, there was part of a strategy actually was to move these chemicals into as many products as possible so by the time this story ever came out, one of the arguments that could be made is, "This is too big to regulate now."

Tristan Harris: Right. It's in everything.

Rob Bilott: There's so much contamination. And essentially because we've been so good at contaminating the entire planet, you can't hold us responsible for any of it. And that's become a real problem.

Tristan Harris: It's almost like intentional entanglement. Fossil fuels are entangled with our global economy, so we can't pull them out. Social media is entangled with elections and politicians and journalism and kids' development. We can't pull it out now. It's entangled with GDP, it would take down our whole GDP to regulate social media. So this sort of intentional entanglement is kind of one of the games here.

Rob Bilott: Believe it or not, you can actually see these arguments being made in presentations going back decades where the regulators and the lawmakers are told, "This is too big for you to take on. This is too big for you to start regulating this or controlling this because you're going to shut down the economy. These chemicals are so vital now to every sector of our economy that if you tried to do something now you're going to destroy the American way of life," or, "You're going to shut down the world as we know it." When the reality was, unfortunately, this was a very purposeful strategy to move these chemicals out into all these materials.

So what happens is you get to the point where, yeah, you've got folks that are estimating trillions of dollars to address this problem, but you've also got massive impacts to public health and the environment. Who's going to win in that balancing act?

Sorry, I forgot to answer your other question, which is about the drinking water standards. When we finally got the story out and we finally have the US EPA announce drinking water standards, they're saying for two of these, for example, PFOA and PFOS, no more than four parts per trillion to be allowed in the US drinking water with a goal of zero. Now, four parts per trillion is not necessarily the level whether it's safe or anything, but it's essentially the technologically achievable level. So at the level that you can actually detect it down to.

So you're talking about levels where if the stuff's in the water, there's a concern. So it took all of these years to get the information out to where now you have the top agency in the country saying essentially, "If it's in the water, it's a problem," and finally adopting those rules. And then what happens? The companies have now sued the EPA to stop those rules from going forward. And that litigation is now pending in the courts.

Tristan Harris: So I think the stat, by the way, for the four parts per trillion, first to give listeners an understanding, that's equivalent to one drop dissolved into several Olympic-sized swimming pools. So just one drop of PFOS in several Olympic-sized swimming pools is the limit. And that tells you something. And there is this thing we should say, which is all technologies are a Faustian bargain. They give us something, but they also take something else away.

And there are trades that we have to consciously make. I think that's kind of the point of this conversation. If you said to me that we're going to introduce a world of some material that's going to help us store food, keep it safe for longer, have very cheap packaging, dropping the cost of things for regular people by 50% or something like that from whatever it was before and the other side of that is your life will on average be shortened 10 years from cancers. That's a trade that you can imagine... I don't know if I would make that trade, but many people might make that trade because we prefer it.

The challenge is that the harms are now public to everybody, and it's not just an externality that hits my body, it's making a choice for me. I'm making a choice for everybody. And we never consented to this choice in the first place. And moreover, we didn't even know there was a problem, and all the research was hidden to us. And so I think this is the big tension. I wanted to also share a stat that I read from a ProPublica article that a team of NYU researchers estimated in 2018 that the cost of just two forever chemicals, PFOA and PFOS, in terms of disease burden, disability, and healthcare expenses, amounted to as much as $62 billion in a single year. And I think just like the banks, they're sort of too big to fail. They're sort of too entangled to switch out of and I feel like this speaks to... Humanity has to get good at making these harder righter choices when we need to swap something out for healthier alternatives, even if it costs us a burdensome amount of money.

Rob Bilott: Absolutely. And I think that you've hit on another critical piece though, which is the ability to make a choice. As you pointed out, none of us even knew this contamination was occurring for decades and decades. None of us had the ability to make any choice because we didn't know that this was even happening. None of us knew our children were being born pre-polluted with this stuff. We're only finding that out now and after those choices were made for us and those costs were pushed on us.

Tristan Harris: That's right. Well, and so what can listeners do who care so much about this, both for their own lives and in helping making systemic change? And I do want to recommend that everybody should see the film Dark Waters and The Devil You Know. Is that the one?

Rob Bilott: Right. The Devil We Know is a documentary. Dark Waters is a feature film with Mark Ruffalo, Anne Hathaway, and there's actually a new film, also a new documentary coming out that focuses on what 3M knew about all of this called How to Poison a Planet. We had the premiere in New York with Mark Ruffalo here just a couple of weeks ago.

Tristan Harris: Wow. And of course, your book, Exposure, is also another avenue for people to raise awareness. You said in your previous interviews that the power of this film, Dark Waters, really has had an impact at shifting this public demand and forcing the EPA to start doing something about this. And so I think one thing listeners can certainly do is help more people see it, just like I've seen the power of the social dilemma impacting millions of people. So what else can listeners do both in their own lives and how can they protect themselves and also demand more systemic change?

Rob Bilott: Yeah, absolutely. I think one of the most important things is to do what we're doing here, which is talking about this, getting this information out so that people understand what choices they may have now, or at least be able to have input into this. Because I think if anything, what you see from the PFAS forever chemicals story is the power of individuals standing up and speaking out, that people can say, "No. Wait a minute, even though we've always done it this way, that's wrong. This needs to be changed. This isn't working or this has caused some unintended consequence we didn't know about," that it can be changed. And we're seeing that with this PFAS forever chemicals story.

We're seeing how people like Mr. Tennant in West Virginia was able to stand up and say, "This isn't the way this should work." And it took us a long time to finally get to the point but we are now seeing laws change. Laws are changing, not just here in the US, but across the planet. Companies are changing how they make products. We are seeing actual visible change happening because people talked about this and because people are saying, "Yeah, we may have always done it this way, but that's not the way we should do it," and let's find a different way to do it.

Tristan Harris: And what are some of the other ways that people can protect themselves in their own lives while they're waiting for some of these laws to be passed? I want to both emphasize the changing... I always joke from Al Gore's An Inconvenient Truth film, change your light bulbs to solve climate change. Well, change your light bulbs, but also change laws. I think personal responsibility, not the responsibility, but the personal choice that we can make. What are the products that we can switch to from the products that we are using? And then also, how do we demand those laws in our own states and governments nationally to help make this change happen faster?

Rob Bilott: Yeah. Well, as far as the products themselves, it's not easy. It's not an easy thing to find out where these chemicals have been used because at least in the United States, these have been unregulated for decades and they've only started to become regulated in limited ways here. But you can start looking for certain buzzwords in products like waterproof, stain resistant, greaseproof, and those are the kinds of places these chemicals have been used and reach out to the companies that are making these things or selling these products and asking them, "Do you use this stuff?"

There are organizations out there that are trying to make information available to the public, folks like the Environmental Working Group or Green Science Policy Institute. They've got lists of different products and different companies that have committed to move away from these. But the consumers acting together, speaking out, it is making a difference. We are seeing companies respond to that in real time.

Tristan Harris: One of the things that we talk about often, we always reference this quote from E.O. Wilson that, "The fundamental problem of humanity is we have paleolithic brains, medieval institutions, and God-like technology." And one of the problems of our brains is that when you think about forever chemicals, they don't hit any of our evolutionary instincts. I can't smell a forever chemical. I can't see a forever chemical. I can't pick it up with my opposable thumbs in my hand.

And so because it is outside of conscious awareness, by default it will be invisible. It's like just this drive by externality that's we're immersed in constantly. And the only way that we act on it is if we put on this sort of heads up display that augments our perception by listening to this podcast, by watching Dark Waters to make the invisible, not just visible but visceral. And I think that visibility of those harms is what drives the change. And so we need to have repetition. We need to have these things systematically confronted to us so that we can actually act on them, not 20 years later, but now. And with AI, later means now because the field is moving so fast.

Rob Bilott: Excellent point. And with the forever chemicals issue, part of the problem for so many years in my view was the fact that, like you said, nobody could understand or even pronounce perfluorooctanoic acid or have any idea of what you were talking about when they heard those words. You couldn't see it, smell it, taste it, touch it. It meant nothing. When the term forever chemicals started to emerge, I think people finally started to understand why this was something to pay attention to. And then of course, as a lawyer, it took me a long time to figure out how to translate this issue in a way that people could understand and understand why it's important to them to do something about it.

Tristan Harris: Well, you're a brilliant communicator. And as someone else who values the power of language, just want to say, I'm so grateful for your time, Rob, so grateful for what you're doing in the world. So grateful for the 20 years that you have been working on this, that I'm sure thanklessly for a lot of time before Mark Ruffalo gets to play you in a major film. As someone else who cares deeply about the public health of humanity and getting technology and our relationship to it right, just deeply appreciate those who choose to dedicate themselves to the harder, righter thing. So thank you so much.

Rob Bilott: Well, thank you. It was a pleasure talking with you.

![[ Center for Humane Technology ]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!zQw4!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Feeb3c25f-26ad-4fcb-b5b4-aa265d0b8dcf_1063x1063.png)

![[ Center for Humane Technology ]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ZIuW!,w_152,h_152,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6fd8e5d3-c05a-45b0-83a4-53dcc52535b2_1050x700.avif)

Share this post