The status quo of tech today is untenable: we’re addicted to our devices, we’ve become increasingly polarized, our mental health is suffering, and our personal data is sold to the highest bidder. This situation feels entrenched, propped up by a system of broken incentives beyond our control. So how do you shift an immovable status quo?

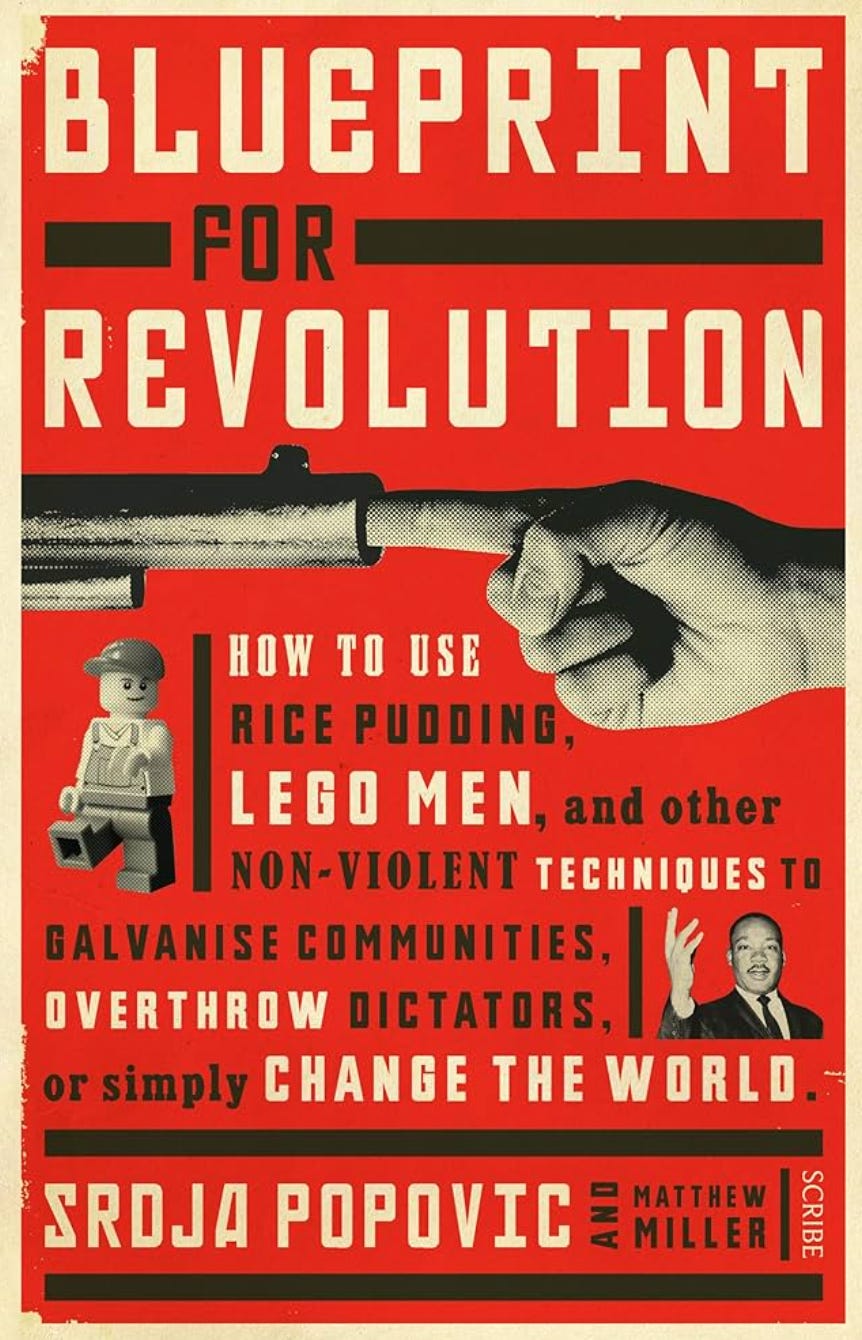

Srdja Popovic, has been working to answer this question his whole life. As a young activist, Popovic helped overthrow Serbian dictator Slobodan Milosevic by turning creative resistance into an art form. His tactics didn't just challenge authority, they transformed how people saw their own power to create change. Since then, he's dedicated his life to supporting peaceful movements around the globe, developing innovative strategies that expose the fragility of seemingly untouchable systems.

In this episode, Popovic sits down with Daniel Barcay to explore how these same principles of creative resistance might help us address the challenges we face with tech today.

This is an interview from our podcast Your Undivided Attention, released on January 16, 2025. It was lightly edited for clarity.

Daniel Barcay: Hey everyone, this is Daniel Barcay, Executive Director of the Center for Humane Technology. You've heard my voice recently as co-host on this podcast, but I wanted to reintroduce myself since I'm hosting solo this week. Like Tristan, I come from a career in tech and actually, Tristan and I met at Google while I was working to build Google Earth. I've also worked with venture capitalists and helped run a satellite imaging company called Planet Labs that helps us make better decisions about our changing world. The larger theme of my career has always been around helping make the invisible visible, building technologies that help us understand our world around us and help us make better choices. And that same motive is what led me to work here at CHT, helping to shed light on the incentives and the psychology that shape the rollout of our technology and hopefully to help us arrive at a better technology ecosystem.

Today's episode is one that plays with these questions in an unexpected way. I've always wondered, we're living inside of a system of incentives that really doesn't serve us and even sometimes actively harms us, addicting us to our phones, causing mental illness in our kids, polarizing our society into these cults and selling our data to the highest bidder. So why do we tolerate it? Why is the system so seemingly stable the way that it is, and why is there this cohesive social movement demanding change? Well, our guest today has looked at these questions from a very different angle of people living under repressive government regimes around the world, and what drives the kind of nonviolent social uprisings that led to their downfall.

Srđja Popović was a part of the resistance that overthrew the Serbian dictator Slobodan Milošević. And since then, he's dedicated his life to supporting peaceful revolutionary movements around the globe through his organization CANVAS, the Center for Applied Nonviolent Actions and Strategies. He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2012 for his work supporting the Nonviolent Resistance in the Arab Spring. Srđja realized early on that a harmful status quo succeeds when it convinces people that one, they're alone. And two, there are no alternatives. In Srđja's work, good social movements can use humor to erode the legitimacy of even the most entrenched autocracy. And I wanted to talk to him because I think we can draw some inspiration from his playbook and maybe apply some of his ideas as we try to draw attention to and question the powerful dynamics behind the AI rollout. Srđja, welcome to Your Undivided Attention.

Srđja Popović: Good to be here. Good to see you, Daniel. And no, I'm not a person who will answer this complicated question. I'm that guy who cannot turn off notifications from X.

Daniel Barcay: Yeah, well, that makes two of us sadly. So I want people to get to know you a little bit. As I spoke about at the top, you were a key part of the Serbian resistance movement that led to the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević. Tell us about that.

Srđja Popović: Well, first of all, good to be here. Good to be with your listeners and just to raise this large expectations. When I was 19, which was about the age when I got engaged in activism, I was actually anti-activist. I thought that activism is for old ladies who are fighting for dog's rights or some bizarre thing like that. But then we had this very bad guy called Slobodan Milošević come into power, and within a few years, the country fell apart. We moved from Yugoslavia to six small ridiculous countries. The high inflation kicked in. My brother had to leave the country together with hundreds of thousands of young people, and basically, everything I knew as a normal world fell apart. Faced with that, as a young person, you have two choices. You can fight or you can flee, and Serbs are stubborn people. So we stand back and fight.

Fast forward, within six or seven years, I went from a street organizer to somebody running the student movement, somebody running from a city office all the way to illegal movement called Otpor, which was officially proclaimed by the Serbian government as a terrorist organization, which was basically labeled for everybody who was anti-Milošević at the time. We grew from 11 people to 20,000 people. We had this very interesting strategy of mobilizing youth and being cool and cocky in the same time, and that really worked and we grew to 20,000. Eventually, in 2000, we mobilized people to elections, we persuaded opposition to run together. Finally, Milošević was defeated late 2000, so that was an instant eight years of my life at one point. But the basic is yes, you can do it, and we figure out we will do it when we figure out that there is nobody else to do it for us.

Daniel Barcay: I think what I love about your story is not only that sort of persistence and that we can do it, but you found these incredibly unconventional tactics that you use to make this happen. Can you talk about some of the approaches you found in that time?

Srđja Popović: Well, first of all, Serbs are not really serious people. So trying to be witty, trying to be humorous, trying to mock everything is a kind of our national mentality, and that works great within the world of the activism. We were facing somebody who was what we would be probably categorizing today as a dictator light or diet dictator kind of that category where you would arrest people but he will release people. He was not really Assad putting people in mass graves, but as he was losing support, he was growing more authoritarian. Eventually, he arrested 2,500 members of my movement only in year 2000. So he was also this gray bureaucrat, and because they were so boring and so serious in their language smelled like that, we figured out, oh, we want to be different. We want to be witty and because of our age, it was kind of very appropriate.

We were also very much rock and roll movement. So what we were doing a lot was experimenting with different tactics ranging from graffiti, slogans, eventually ending in understanding this pattern in which if you do something witty and you hit the right target, then your opponent will respond and then they will become the part of the show. And this thing which we later labeled as a dilemma action and build a whole research on a website called Tactics for Change, which is we are very passionate now to figure out how it works in different other countries, but understanding that you can be witty and you can do something really humorous like making a cake for president's birthday and then make a big mock out of it, invite journalists, and then the police arrives.

Put the face of Mr. President on a petrol barrel, invite people to hit him with a baseball bat, and pay 25 cents in Serbian Dinars to do it, and then see what is going to happen. A lot of this was experimentation and it contained this amazing part of dilemma where your opponent has only two bad choices if they react to your prank and do something inappropriate as arresting the petrol barrel and taking it to the police station, which actually happened in the real world.

Daniel Barcay: Wait, so slow that down. You mean that you literally just have a barrel?

Srđja Popović: Yeah. Yeah. We were pretty poor at the time. We were a group of 15 people, so we got the old petrol barrel or gas barrel or oil barrel, I don't remember what was originally in it. And we had this artist who made an amazing face of Milošević on it, and then there was a hole on the top. So like in a pinball game, and I don't know if your listeners remember, but there were actually video games where you put a coin and you can play a video game. So it was very much along the line of that.

So you earn your three hits, like the three balls in the pinball. So you put the coin in it and immediately you gain right to do boom, boom, and boom like three times you hit the face and express your love for Mr. President. And amazingly, we put this in a main pedestrian zone. I think that was the coolest part of it, was that we invited non-political people to deal with it. So this was not us doing it. It was not opposition activists doing it. It was like just this little great experiment where you really check what people will do with it.

Daniel Barcay: So you're saying the police arrested the barrel, is that what you're saying-

Srđja Popović: Oh, yeah. What actually happened was that we put this barrel in a Belgrade version of Fifth Avenue, and basically, the idea was to see what the police will do. And the funny part was when they arrived, they were looking for us, but we were nowhere around. And then they were looking at the barrel and there's this mutilated face of president getting swollen more and more after a lot of these beating. And eventually, because they got the command to stop this thing, they had to arrest the barrel. So they dragged the barrel into the police car, and of course, everybody pulled the camera out and start taping them and they become a punchline. But the genius behind is the thing that we figured out by being creative, you are making your opponent's strength working against him or herself, and in this case, police was the most important part of the Milošević oppressive machine and making them look ridiculous carried an extra value for itself.

Daniel Barcay: That's a dilemma, right? I imagine the dilemma is they arrest the thing and they look ridiculous or they don't arrest it and then they look weak.

Srđja Popović: Absolutely. So this is when we start studying this, we figure out that this is not a new concept, but also making one step back. The dilemma actions work when they're made against the wildly held beliefs. Probably the best-known historical dilemma action is Gandhi's salt march and this idea that Gandhi will march to the sea to make salt because the Brits were banning making of salt and they wanted to tax the salt. Everybody needs salt makes no sense to tax salt in India. India can produce their own salt. I mean you, Daniel can produce your own salt. And of course, Gandhi was the master of drama. So he started from Dundee with 60 people, ended up having 20,000 people doing this, and he wanted to be arrested. His idea was like, okay, if Brits arrest me, I will walk out on a 50-pound fine after three days, that was the fine, and then I will be the national resistance leader.

If they don't, everybody will make salt. So this idea, if you don't react, you'll look weak comes with a replicability. Recently we found 450 cases of these across the globe, and you type in www.tacticsforchange and they're all there and they're everywhere and they're in Africa and they're in Latin America and they're around everything from human rights to environment, all the way to potholes. And the beauty of these dilemma actions, once again, there are so many creative ways people were treating the least political, the least inspiring problem in the globe, which is potholes, this different tactics that people were using around the potholes, and some of them are as hilarious as our barrel.

Daniel Barcay: I think it's important for our listeners to understand that while you didn't invent this tactic, the thing that you did is you brought all of these different examples together and you gave it a name and you called it laughtivism and you called it dilemma actions. And the work that you do at CANVAS has been really critical in showing people that this is a field. This is not just nonviolence, this is beyond that. This is doing things to use humor, to use double binds, to pull things that people think they already know into the public consciousness. You have a few other stories. I wonder if we can quickly go through them like the ping pong balls or the Lego protest. I think it's important for people to see a few of these examples.

Srđja Popović: There are people in Syria actually opposing Assad in a nonviolent way, which came out with the two amazing things. One of them you can see in Everyday Rebellion movie, it was really taped on a camera, which is this idea that we make a little red ping pong ball symbolizing the dead people Assad is leaving everywhere, write the messages of freedom, and then cast like 2000 ping pong balls down the stairs in Damascus. And then the police have choice between leaving this ping pong balls so people can take them home and get inspired by revolutionary message or somehow collect 2000 ping pong balls and that's a big deal. But that was just the beginning. And then they understood that this thing is driving police crazy. So it came with something even worse. It's like they had this song which was a revolutionary song in Syria, which was banned by the regime and highly discouraged.

So they somehow figure out to use the technology, if we can call this technology this very cheap musical chips, which you can buy from China and teach the chip to sing that song. So you order, it's probably cost two bucks and they put a little song with a little chip, with a little on a lighter, these Chinese singing lighters, they're annoying and they're constantly singing that one melody, which is highly discouraged. But what happens if you hide them in the garbage cans? What the police will do, they will let them sing the song or they will get the order to stop this, which will make the police digging through the garbage. And now it's like-

Daniel Barcay: And it's not just about the police digging through the garbage, right? It's about the police are clearly not doing their real jobs. It's about the police are doing something not only foolish but wasteful, but against the-

Srđja Popović: The big part of this is exposing this. One of the reasons when we were looking into why dilemma actions work, and this is where Penn State came in, and amazing Sophia McClennen that I must mention here, who is the American expert in political satire. So she understands how this playful satire actually work. And it was her making this breakthrough thing to understand. This is the reason why this work is exactly as you mentioned, Daniel, is because you are exposing the stupidity, you are exposing the bizarreity, which means in normal countries, police chase drug dealers. If they're chasing the Chinese chips singing certain melody from garbage, there must be something wrong. Getting us back to the Russia in 2012 after stolen elections in small places where protests were banned, people were organizing protests of toys. So they would or bring their Lego and things of that kind into the village. It happened in Barnaul, Siberia taped somebody make a documentary about this. And the funny things like day one, you see the police and the people. This is 4,000 people village-

Daniel Barcay: Wait, wait, let's back up because I really love this one and we've got a lot to cover, but you should talk about what it means to have a Lego protest.

Srđja Popović: Okay, so you want me to tell the whole story about it, right?

Daniel Barcay: Well set the scene just a little bit, it doesn't have to be the whole story, but set the scene. What does a Lego protest mean?

Srđja Popović: Okay, so 2012, it's a year when Putin won elections and he would probably win them with two-thirds, but for some reason, he wanted to win them with 82%. So his guys were caught stuffing ballot boxes and that always sparks a protest. It's always a powerful trigger and clever as it is, the Putin government let people protest in St. Petersburg and Moscow where the cameras are, but they wouldn't let you protest in the small places. So there's a small place called Barnaul in Siberia in the middle of nowhere, people came to the idea that they'll bring their Lego toys, but their toy soldiers, toy cars, and they build a little protest in a downtown or down village it's probably more appropriate thing. It's a very small square with a little thing under the tree. And they put these little Lego things and they had this little transparent saying, oh, 136% for Putin, give us free and fair elections, things of that kind. And the whole thing was like two square meter big. This is-

Daniel Barcay: You are talking about little people two inches high with little signs, three inches high.

Srđja Popović: Very small. Yeah, very, very small people, very plastic people, very small animals, very small cars all of these things are... The whole protest will probably fit into your living room. And then the people are around this thing and they're bringing toys and they're having fun. Everybody knows everybody. It's a small village. All three policemen in the village are there. Everybody talks to everybody, everybody's taping it. And I've seen the footage of it. And then the funny thing is when it goes uploaded on YouTube, once again, technology, one of the ways that technology helps movements is give them a life of their own online so people can see it and they can replicate it. One of these views is from of course, from Kremlin or from FSB, and they're looking at it and they understand what it means. It means that it needs to be stopped because everybody has... Like I can build a whole protest myself.

I have two kids, so it's like they need to stop it. They call the chief of police. So now the chief police of Baurnal, once again, police should be protecting law and order. This is how we imagine police. The guy need to stand in front of his fellow citizens and TV cameras and make the probably most stupid statement in the history of law enforcement stating that a scheduled protest of 50 toy soldiers, 30 cars, and whatever, [inaudible 00:16:43] is banned because by constitution, only citizens of Russia can protest and toys are made in China.

So once again, this also comes with a great exposure because people are not stupid. They understand what this means and when they do this is Putin for God's sake. The guy who loved posing shirtless wrestling tigers, saving dolphins from drowning, but he's afraid of toys. And now this thing is the dilemma, and for some people, this works for some not, works better in dictatorships, but once again, it's your thing to do it and then it's your opponent thing to react to it, and then how you capitalize it. This thing ending on the cover page of a Guardian, one of the largest European newspapers, it will never end on the cover page of the Guardian if it wasn't banned.

Daniel Barcay: Right. Right. And so part of what I love about this is not only does it expose how many people have latent support for this, not only does it show how ridiculous it is that people are shutting it down, but there's something about humor itself. There's something about the fact that even telling this story, I've probably heard this five or six times from you and I still laugh and there's something beautiful about that. It's like the laughter itself is a humane way of dealing with a really difficult topic, right? It's like you're taking a really hard topic of what is possible and not for political change, and you're bringing it so concrete down to this is ridiculous.

Srđja Popović: I think Daniel, that this also has to play a lot with our human nature. And if you imagine the social change as a video game and look at the engine, the engine of change is enthusiasm. So you want to bring enthusiasm and mobilization up and you want to bring the fear and apathy down. The main preservance of status quo in a video game called social change is either fear and dictatorship or apathy in a different type of society. Humor magically has power to deal with both. Humor breaks fear. This is the nature of the psychological beast. Second apathy, imagine going to the most boring part in the world, and then immediately the social prankster comes in and she or he is the person who can make you laugh and she or he's the person who can make everybody laugh. And then you want to stay immediately.

And when you add a social movement component, you understand that it also comes with a cool other things and people love being around the cool things. One of the reasons why people are joining Serbian movement, one of the reasons why people were joining social movements everywhere because they're cool, and if you can make your movement be cool, then you're appealing to the normally non-political people who want to be around the cool kids and you are the cool kid.

And so that enables you to reach to the people that you really want to mobilize, which are the people with fresh idea, which are the people who are not ideologically poisoned from the left or from the right and who are not the people who non-stop talk politics, so nobody listens to them. So this is also your mobilization tool. It's not just the tool to make your opponent look ridiculous. It's not just the tool to break the fear. It's not just the tool to break apathy. It also shows amazing results and our study shows that if you use the dilemma actions, you're more likely to recruit more people, not only to get more media.

The main preservance of status quo…is either fear and dictatorship or apathy in a different type of society. Humor magically has power to deal with both. Humor breaks fear. This is the nature of the psychological beast.

Daniel Barcay: So I completely believe this, but one of the deep questions I have is we talk about the use of humor in driving political change. My read on history right now is there's online, there's a lot of different uses of humor all over the place in politics, even in the US, both sides are using humor, but sadly it's not the kind of humor I think you're talking about. It's the kind of humor that misrepresents the other side. It's the kind of humor that sort of is about painting the other side as really not cool painting whatever your side is as the cool people you want to be with. And I'm wondering, I feel like the way that I see humor right now is destructive to politics, at least in the American context. Can you talk about the difference between humor that really elevates the conversation that you're talking about and the humor that detracts from it?

Srđja Popović: This is a very important question and we'll try to outline it throughout the lines of polarization, which I think is a detrimental force to the human agency. It's detrimental force to democracy, and it's unfortunately one of the worst byproducts of using technology and social mobilization is putting us in these silos where we only listen to the people who are like us and not even hearing and tending to despise without hearing the people who don't think are like us, whoever they are, and we didn't even care who they are because we don't see them. When you exercise political tactics, one of the things you want to have in mind is how to avoid alienating the other side. Unfortunately, political parties in US, unfortunately, political movements in some other places are using a lot of these we are talking to our own crowd, or how it's politically called. We are consolidating our base or something like that. Eventually-

Daniel Barcay: And that's what social media did to our society.

Srđja Popović: Oh yes.

Daniel Barcay: You're no longer have having to speak to everyone.

Srđja Popović: Oh yes, that's a big problem with the social media algorithm is that the more you consume, the more you believe the whatever climate change is, a Chinese hoax, the more anti-vax context you will also get. So it's like it comes in packages, the people are put in silos, but to break the silo, you want to understand that the people are in the middle, and in order to really win in nonviolent struggle, you need to win the middle. Every successful social change movement in history started from extreme and ending up in a mainstream. And I think this is the message we lost in the meantime. It was not the Black people who won the civil rights movement. It was the Black people combined with some other people. It was not LGBTQ people who won the LGBTQ rights in US.

It was the LGBTQ people plus some people like you and me who believed that LGBTQ people have equal rights as everybody else. The environmental movement started as a bulk of crazy hippies tying themselves for the fences of the nuclear bases in '60s. Now you don't have a decent state which doesn't have the Ministry for Environment, Environmental Protection Agency, or some very mainstream thing here. You win in football by controlling the middle field. So very similarly winning nonviolent struggle when you can appeal to the middle, when your ideas can appeal to the middle, where your tactics can appeal to the middle. And yes, when your humor can appeal to the middle.

Daniel Barcay: I've got to say that this is really justifying for me because at the Center for Humanity Technology, we really... All these debates are so highly polarized and knock on wood, we really try to make sure we're in a position where, for example, politicians on the left and on the right consult us and ask us to help frame what's going on. We try to find our solutions in frames that this should be completely above any sort of political divide. And yet to your point about a missing middle, forget about left-right. The AI debate is so flooded by either it's shut it all down or it's run towards the beautiful future and take off all the brakes. And we're trying to hold this place where I believe there's a tremendous missing middle that needs to say we need to do this a lot more carefully with a lot better understanding of what's happening.

Srđja Popović: I'm with you on this one. I think understanding is from the point of social change, from the point of social movements, the internet technology, the social networks, the AI, it's not different than the nuclear energy. Nuclear energy is this thing that you can use to heat up the rooms with newborn babies and you can also put it in a bomb and throw it on a Hiroshima. The internet can be used to polarize people and make them hate somebody or even want to kill somebody or radicalize people and having them ending up in ISIS-type of groups. In the same time, this is the place where amazing things can be spread, people can learn from each other, and can be used for social mobilization, organization.

AI is the thing that everybody talks about how they can produce the deepfake videos and within the range of months, you will have somebody looking like Barack Obama giving you racist comments in a deepfake video on the internet and millions of people are sharing it. It's like understanding the power of technology, but also its limitations. Technology per se is not good or bad. It is how we use it. In the same time, I've spent better part of last month taking a look with some amazing people, how you can use AI to fraud-proof elections. There are so many different things that you can use for it then it's like it's very difficult to say, oh, it's here or it's there, or if it's left or it's right.

Daniel Barcay: It's both. And it's confusing, right? It's confusing because it is both and you can't let your mind's desire to say it's so simple. It's either one or the other. It's both and I think this is where I wanted to really get your understanding because we're not in the game of trying to overthrow a political opponent or a dictator, and rather we're looking at a bunch of economic incentives. And with economic actors, it's not even necessarily one economic bad actor or two or three. It's the overall incentives creating this system that a lot of people feel needs to be more responsible, needs to change. And yet the system feels a little stuck. And I'm wondering if you've dealt with these same tactics and how they apply to economic actors, not political actors, and how that might be relevant.

Srđja Popović: The social change theory of CANVAS really work on any kind of institution and very often the institution you want to address are economic institution. I will remind you that some of the largest and most effective changes in US, one of them I recently mentioned, which is the civil rights movements, was using attack on economic institutions and bus boycotts, for example, as a tool to gather desegregation in other parts of society. Some of the largest and most inspiring things in US came through the idea that you should be influencing economic institutions, large and small. Plus some of the largest thing that happened in dictatorships is making institutions work slowly or not working at all or using tactics as non-cooperation and general strikes. So the answer is yes, Daniel, you can use the theory of change to strategically impact the institutions and about-

Daniel Barcay: Well, hold on. Can I back you up a little bit, which is one of the things I was hoping for? The thing about strikes and some of these sort of traditional non-violent actions is they lack that sort of spark that some of the laughtivism and dilemma actions have that sense of humor and that sense of everyone just sees something that is so true that it's funny. And I'm wondering if you have any stories or examples of economic systems that have changed in that sort of laughtivism way.

Srđja Popović: Well, I won't go further from United States and a group of people that I love and admire and I'm proud to call my friends, that's a very small group of pranksters called the Yes Men. And outside of making a really good toolbox for activists called Beautiful Trouble and teaching amazing workshop in New York, they're also known for some of the coolest ways to mock corporations. Several years ago there was a big scandal about the Volkswagen, which is German company, which also sells cars in US, and they were basically faking their emissions. So there was this idea that diesel engines are great, but actually they were not so great and this moment in time when everybody was talking about this, but as you said, nobody was doing anything cool about it. People were outraged, people were farting on social networks about this and fuming around. But then the Yes Men stepped in with something really amazing, they did a fake press release where Volkswagen actually apologizes for the worst things that they did with their emissions.

Daniel Barcay: I remember this. I forgot about this one-

Srđja Popović: And now back to dilemma if you're Volkswagen, what the heck will you do? So will you say, "No, this is not my apology. In fact, I'm not apologizing for what I have done in cheating millions of people and taking their money while screwing up the climate." Or you will say, "Oh, these guys are right, we should have apologized earlier and actually give them the gold medal." So corporations as well as government can be caught in some kind of bizarre cheat and this is not the rare situation.

Daniel Barcay: So at risk of taking advantage of this podcast and getting a little free consulting, I'm curious how you would think about what we're doing here at the Center for Humane Technology is it is really trying to highlight some of the absurdities inherent in technology and obviously there are these very serious topics of polarization and addiction and distrust and undermining of democratic institutions and then AI eroding our sense of what's even true. Do you have any advice on what it is to bring these sorts of campaigns directly to the field of technology to point these out?

Srđja Popović: Well, it's very difficult to name one thing because it's like a climate change fighting for fair technology. It's a very big thing. I think that you need to think big, but you need to start small. You need to pick the thing which outrages you the most or you think it's the most counterproductive. I figure out that, for example, hate speech on the internet is something that causes a lot of trouble. And figuring out the ways how to make this either more regulated or more hilarious when it's not regulated. So it's like exposing the stupidity of the fact that if I say... I can tell you exactly how I can make 50 trolls outraged now on X. I can take my phone now and I'll say, "Okay, this is what is going to happen."

I'm going to post something and I will cause every single Russian troll who follows Georgian protests to go after me and they'll all be based in Serbia and they will be speaking my language and there'll be 70 of them and it's all empty phones. These are not even the people. So figuring out what really outrages you and targeting one thing at a time and then exposing how ridiculous it is by maybe overusing it. It's like if you do this enough, it may turn into the network trying to regulate this or trying to solve this problem. So instead of crying out loud, you can make a funny way to expose the problem and I just show you the funny way you can make a little video. You can-

Daniel Barcay: There's a fine line between playing into the harms of social media and pointing out the harms of social media-

Srđja Popović: Yeah but that's it. That's it.

Daniel Barcay: We actually grapple with this every day. How clickbaity do we get with our podcast episode titles? It's sort of this weird position where you don't want to be the one who's playing into the machine and yet to your point-

Srđja Popović: So you're using a machine. Yes.

Daniel Barcay: Yeah. There's something about using it in such a ridiculous way that help point it out-

Srđja Popović: Yeah. But it needs to be ridiculous. It needs to be funny, it needs to be cool for people to follow. But to do it, you need to pinpoint concrete things and build around the concrete things. And once again, you want to take the concrete things which are less controversial. So it's like the thing I mentioned outrages the people from left and right and center completely. So it's like you can really do it in a real-world and you can really expose how these things are ineffective instead of saying, "Oh, we need to regulate this and we need to blah, blah, blah," in which case nobody will listen to you and you'll alienate 80% of the people.

Daniel Barcay: That's right. Well, and I actually want to go back to something you said at the beginning, which I can't remember the exact words, but it was like the two main enemies of successful engagement are apathy and fear. And there is this way in which trying to get over apathy, trying to rattle people to get them out of apathy creates fear. And now you're stuck in a different problem and it very much resonates with what you're saying. And one of the ways we've tried to do this is trying to get people in a place of we actually can do differently. This is going to take a lot of effort, but we can all push for these better futures in a way that doesn't feel like we're just asking people to shake terrified in the corner.

We're working on that. And to that extent, I think there's an interesting puzzle because on one hand you can point at the stuff that people already know and already feel or you can point at the bigger problems that we think are coming in a year or two or three. And what we're trying to do is to make good demos that bring some of those things that we're talking about, making them real to people and allow people to think about them, to act on them, to process them, to ask what is a better way out of this quandary?

Srđja Popović: We must not forget that the reason why the post-truth world is so dangerous, and I will point to another great book called This Is Not Propaganda by Peter Pomerantsev, I always advertise my friends. He's playing with this idea that the modern propaganda of the bad guys, which is very effective on the internet and conspiracy theorists, they're not there to promote one point of view or another. They're there to kill human agency because idea of a conspiracy is that there is something bigger than you, like X-Files type of thing. And there is always a Bilderberg Group or a CIA or whatsoever somebody is pulling the strings and there is nothing in the world the two of us can do about it and that promotes apathy.

So the reason why you really want to take a look at this and the reason why I like what you do is showing to the people models. It was always a small committed group and the people that made a big change in a world. And yes, all of these systems are stable until they're not and they just look stable until they're not. I mean Assad was damn in power. So the guy who was a serious mass murderer can fall within the blink of an eye. How come this is because they're projecting this idea of stability, but they're not really stable.

Daniel Barcay: Right. And so talk about that a little bit. How does it flip so quickly? So you're saying it's not stable, it's not stable, there's the overhang of people believing that they're stuck with it, but then all of a sudden perception flips really quickly. How does that happen?

Srđja Popović: I will give you the systemic answer in one sentence. There is amazing guy whom I used to know, and his name was Gene Sharp and he was this amazing guru of nonviolent resistance and he explains this very simply. The core of status quo is obedience. If people do not obey, rulers cannot rule. I just walk into the studio of the classroom with 16 students and they were listening to me because, from their own self-interest, they probably told that they can learn something about the movements from me, but if they appear in the same class and they turn their back to me, or if they're appear in a class and they have these earbuds or AirPods and they're not listening, the simple act of non-cooperation can destroy my authority. But the idea is if people do not obey, rulers cannot rule. By themself rulers cannot maintain law and order, make public transportation go on time, or collect taxes.

They cannot even milk the cow. They need services of the people to stay in power. If people disobey rulers cannot rule. And on the other side, very often if you look in these big oppressive systems and the bigger and more oppressive system it is, the more it's likely to disintegrate fast. There was this moment in time in a place called Chile under the gross guy called Pinochet in late '70s and '80s, and this was one of the Latin American military dictators, and this was the guy well known for throwing people from the chopters and being very oppressive. So you couldn't really protest, you couldn't really strike because you will get killed. Then people came to this idea that a small low-risk mass tactic may work, and they came to this day that a certain day in a year, a symbolic day they will all in the same time in Santiago, the Chile.

Which is the capital of Chile, will use the rush hour to walk half speed and drive half speed. So it's legal, it's low risk. Nobody can say who started this. It's user-friendly, anybody can do it. And if I see you driving half speed, I will honk to you and I will wave to you. And this the real-world guy who was participating in this action tells for a documentary called A Force More Powerful. And says that by simple virtue of seeing so many people doing such a simple thing at the same time, we figured out that we are only living in a nightmare and that in fact we are the many and they're the few.

The core of status quo is obedience. If people do not obey, rulers cannot rule.

Daniel Barcay: Okay, so I don't know if you know this, but Dario Amodei, the CEO of Anthropic, one of the biggest AI labs recently invoked your name in an open letter he wrote about the upside of AI called Machines of Loving Peace.

Srđja Popović: Really?

Daniel Barcay: Do you know this? I want to read you the quote because it reminds me of the last riff you were on. So Dario wrote, "Uncensored AI can also bring individuals powerful tools for undermining repressive governments. Repressive governments survive by denying people a certain kind of common knowledge and keeping them from realizing that the emperor has no clothes. For example, Srđja Popović who helped topple the Milošević government in Serbia has written extensively about techniques for psychologically robbing authoritarians of their power, for breaking the spell and rallying support around a dictator, a superhumanly effective AI version of Popović in everyone's pocket, one that dictators are powerless to block or censor could create a wind at the backs of dissidents and reformers across the world." What do you think of that?

Srđja Popović: Amazing. That looks like a very scary future, like the very small version of me into everybody's pockets ugh. I'm just joking.

Daniel Barcay: I mean, planning a birthday party.

Srđja Popović: Yeah, but the idea is there, I think I want to speak to this guy, I don't know how he is maybe I do. I really want to take a look at the most important part of the new technology is teaching people how to do things and making our life easier in some of these extent. On a tactical level, I think the next big thing that CANVAS is up to is training AI to prevent election fraud because a lot of democracy happens in a gray zone of what is the election fraud and what is not the election fraud and how Maduro can survive with stealing elections that he lost two to one and what will happen in elections in Bolivia, and whether we have or we don't have these 11,000 votes in Georgia, and putting the AI in a good use in documenting and making open source voting, for example, maybe one of the best ways tactically to imply AI. Also making this clever things that's part of this is creating a database of how elections are stolen and preventing this by training people on how to prepare in case elections are stolen.

And that's very practical application of what Dario is saying here. And on the other hand, we can imagine how many people Xi Jinping has training AI to prevent any kind of social uprising as we speak. So it's like once again, there is no good side or the bad side on this. It's up to the people like you and me to figure out what may be the good applications and how we can raise awareness and resources and money to put the technology into the good thing. I mean, the other application of new technology is Bitcoin. And as many things in life, I start from the wrong perspective that this thing is a scam and it's normal coming from a place like Serbia and figuring out how it's used to abuse state resources of electricity and not paying electricity in order to mine Bitcoin in order to produce pure money for the people connected to the corrupt government.

And this is one of the applications of this thing. In the same time, a friend of mine, Alex Gladstein from Human Rights Foundation, the Bitcoin enthusiast himself actually brought me to the right side of the things and I'm helping his team to figure out how we can use Bitcoin as a dictator-proof money because one of the first things autocrats do, they restrict access to money to the opposition groups. And now as we speak, the people are using Bitcoin to help humanitarian actions, to help anti-junta movement in Burma, to help now hiding underground the real winners of the elections in Venezuela, and things of that kind because this money is also untraceable for the autocrats.

So once again, every single time it depends on the people like Alex Gladstein or you or me, to figure out how the new technology can be used for the good purposes and then developing successful case studies to persuade those like myself in the case of Bitcoin, that to take a look at this thing and maybe expand it and maybe use it for good purposes. And this is how you move technological skeptics to technological enthusiasts by showing them the good use.

Daniel Barcay: This side of the conversation is we call offense and defense dominant. So you have to understand whether a technology enables more people to attack open society, to create new mechanisms of exploiting or destroying our world, or creates new ways of defending and propping up the world we want to have. And when we can show the technology that it's defense dominant and there's good players doing great things with it, we're on team technology, let's go do that. And so I think we should end the conversation today by giving you a chance to just talk directly to the listeners of our podcast about what does it mean not necessarily to be an activist in the space. Most of our listeners are probably not activists, but what does it mean from your perspective to be awake, alert, and use this moment well?

Srđja Popović: It's difficult to give advice to a lot of people in the same time, but first of all, if you're passionate about something, know it is possible. I think this is one thing that what the previous 20 years of my life working with activists taught me is that even the smallest creature can change the destiny of the world or the destiny of the neighborhood. So if you care for something, then try. Activism is actually very, very pleasant and addictive thing. This very feeling that you can change things gets you to the self-empowerment place. And I think we need more of this human agency self-empowerment in a time when we are too distracted or too overwhelmed or too busy scrolling our screens. Second, there are tools to do it. Some of these tools are offline. Some of these tools are online. Some of these tools are very ancient technology.

When you read the book, when you write the slogan, that's a very offline way to do it. If you use AI, if you use social network, that there is a very technological way to do it. But think of where you are and think of this moment. And if we don't make technology work for us, who else will? The more we are in control, the more we are in the open source of space where we do use technology for our own source. And it can be something like open source money like Bitcoin or open source internet, which I'm trying to figure out right now. Or we just follow the bad things that are happening on the social networks like polarization or hate speech and expose them. There are many ways that we as individuals can engage in this fight. And eventually it matters because we are leaving this planet to our kids and they will live in a more technological and probably less regulated place than you and me are living now.

If you're passionate about something, know it is possible…even the smallest creature can change the destiny of the world or the destiny of the neighborhood. So if you care for something, then try.

Daniel Barcay: Srđja, thank you so much for coming on Your Undivided Attention.

Srđja Popović: Thank you for having me and making this world a better place in a very, very important point. One more thing that you can do is you can learn. One of the great things is that in the world of new technology, it's so easy to find resources online. You can go to CANVAS website and see the cartoon version of how to build a movement in under 45 minutes. And you figure out these things that we're discussing for an hour can be fit in a small cartoon video. You can go to Tactics for Change, which is the website we developed with the Penn State where all of this marvelous dilemma action and activism, they're explained, they're explained how they work, they're explained historically, they're explained through media. So there are a lot of resources that you can use in order to inspire yourself and make yourself active. But it all starts with you and your decision to make technology work for the people. And your understanding that nobody else will do it if you don't do it. So eventually it has to be you.

![[ Center for Humane Technology ]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!uhgK!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5f9f5ef8-865a-4eb3-b23e-c8dfdc8401d2_518x518.png)