Kevin Esvelt: Decoding Our DNA

How AI supercharges medical breakthroughs and biological threats

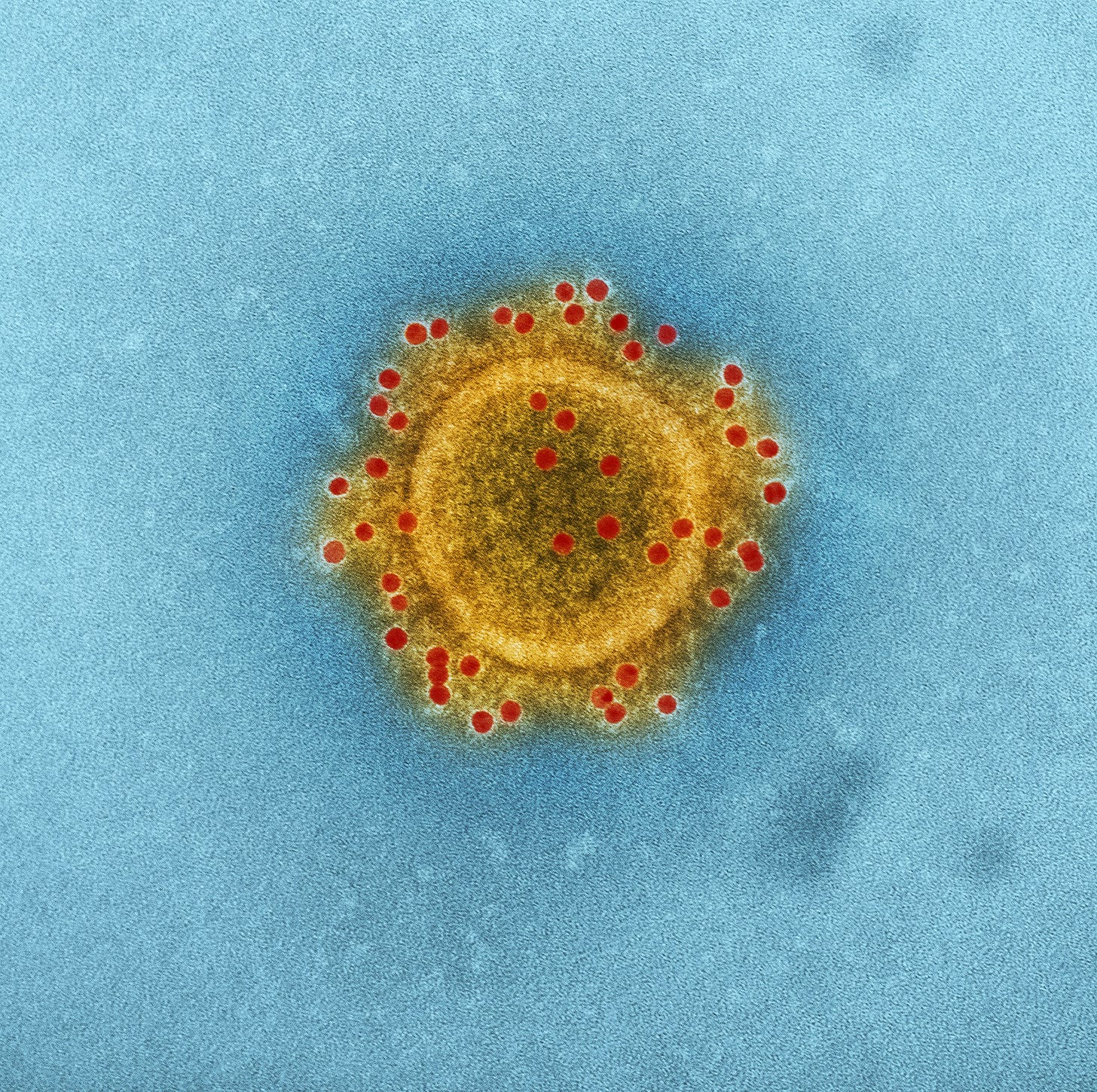

AI has been a powerful accelerant for biological research, rapidly opening up new frontiers in medicine and public health. But that progress can also make it easier for bad actors to manufacture new biological threats.

Biologist Kevin Esvelt joins Tristan and Daniel to discuss why AI has been such a boon for biologists and how we can safeguard society against the threats that AIxBio poses.

This is an interview from our podcast Your Undivided Attention, on July 18, 2024. It has been lightly edited for clarity.

Tristan Harris: When you strip down all life on earth to its most essential parts, it's a language, a language with four characters, A, G, C, and T. These are the four base pairs that make up every strand of DNA. And all of biology is fundamentally controlled by this language, even though it wasn't until 2022 that we sequenced the complete human genome, we're still in the relative infancy of understanding how this language works, and interacting with it is like pouring over ancient hieroglyphics. But now we have a Rosetta Stone, a key that can translate those hieroglyphics for us, and that is AI. We've seen so much in the news about how AI has been able to ingest the language of human interaction and create chatbots or ingest the language of coding and create GitHub copilot, but what gets less attention is that AI is also able to understand the language of our DNA. And understanding our DNA means that we can go from creating powerful language machines to powerful biology machines.

Tristan Harris: Researchers have been able to use AI to model thousands of molecules and proteins in a seconds to develop promising new drug candidates. But these advancements are a double-edged sword. The same technology that enables rapid drug development can also allow bad actors to rewrite the language of biology for malicious purposes. AI is rapidly opening up new frontiers in biology that sound like science fiction, but they're not. And we need to take these advancements seriously. That's why I'm so excited to have Kevin Esvelt on this episode. Kevin has dedicated his career to this topic and he's one of the world's top experts in synthetic biology. He's a professor at MIT and director of the Sculpting Evolution Group. Recently, Kevin has devoted a lot of his time and attention to the threat of AI-enabled biological threats, and he's come up with some really pragmatic and achievable solutions on how we can minimize those threats. Kevin, welcome to Your Undivided Attention.

Kevin Esvelt: It's lovely to be here.

Tristan Harris: So let's dive right in. What is it about AI that makes it such a powerful tool for biologists?

Kevin Esvelt: That's a great question. It's really hard for us to learn to speak the language of life because we just don't natively read A's and C's, and G's, and T's, let alone the 20 amino acids. That's not how our brains evolved. But if we can train an AI to do that, then it gives us access to a capability we wouldn't otherwise have. So we can train an AI, a bio-design tool with a lot of data that we've gathered either on different proteins and how they fold or different variants of a particular gene and the corresponding activities of the protein that that gene encodes.

Kevin Esvelt: Now, proteins are chains of amino acids, typically hundreds of amino acids long, and there's 20 possibilities at every position, which means that a short protein of just a hundred amino acids, there are more possible proteins of that size than there are particles in the universe. So we can't possibly learn on our own how to predict the activities of proteins, but with AI, we can now predict how proteins fold. And if we get enough data, we might eventually be able to design new molecular tools with useful functions in order to fight disease.

Daniel Barcay: One of the things that you did relatively early on is talk not only about all the incredible benefits that this could give us but also the new risks that these tools end up creating specifically in the way that the DNA synthesis machines could be used. Can you talk a little bit about that duality? There's all these benefits, but then there's all these risks as well, right?

Kevin Esvelt: So I'm cursed to always think about what might go wrong. And I'm fairly concerned that as we learn to understand and program biology, we might learn to make pandemic viruses before we can adequately defend against them. And that suggests that we might not want to make it extremely easy for everyone to acquire the DNA that allows them to synthesize an infectious virus because that's one of the things that we can do now. So you can go online and look at the sequence of pretty much any virus that we've ever discovered and virologists have come up with ways of turning that sequence into an infectious virus.

Kevin Esvelt: It's a critical tool in understanding how viruses in disease work and coming up with countermeasures. And it depends on the exact kind of virus, the details of how it works, but what it amounts to is you need to turn those A's and C's and G's, and T's on your screen into physical DNA sequence. So to do that, to turn bits into atoms, you place an order with a DNA synthesis provider, which is just a company whose business it is to turn that string of symbols into a string of molecules. So you order that from them, sometimes with other DNA, with instructions to help make the virus. That depends on the details of the virus. And they send you this DNA sequence in the mail.

Daniel Barcay: And I think a lot of our listeners might not even know that these are fully automated at this point, there're machines. I don't know how much they cost. Are we talking desktop machines or are we talking about $5 million things in the back of a lab? What are these machines?

Kevin Esvelt: That's a great question. So the DNA synthesis machines, there's a whole bunch of them, different varieties. Some of them specialize in making lots and lots of DNA at once in the industrial scale, and those are few million dollars as you said. But you can also pay several tens of thousands of dollars for one that will sit on your desk and it will let you make DNA. So a desktop DNA synthesizer can produce enough strings of DNA to make an influenza virus in about a week. Now, it's just going to make the DNA in pieces, it's not going to stitch them together for you. There's people making machines now that are the assemblers that will do the stitching together automatically. Right now there's usually some humans involved to some extent, but that's gradually vanishing.

Tristan Harris: In your research, I think you say 30,000 people are already able right now to assemble a flu virus, 5 to 1000 people could make coronaviruses and 100 to 500 could make a poxvirus right now. That's way more people than can create nuclear weapons in the world. So this already just sounds incredibly dangerous. Why hasn't this just been locked down to biology labs that have access and you have to be some kind of licensed biology researcher? Why are we even in this state as it is? It sort of seems crazy to me.

Kevin Esvelt: That is a phenomenal question to which despite being in this field for multiple years, I just have not yet worked out an answer. Given the seriousness of which we take nuclear weapons, it doesn't make sense. Given the seriousness of which we take infectious versions of these pathogens and the controls that are necessary to work with them to store them, to get anywhere near them, it doesn't make any sense. But if you think about the Select Agent Program in the United States, which is the program that regulates control of all these kinds of pathogens like smallpox, like the 1918 pandemic influenza virus. In order to work with them, you have to have security background checks, you have to show that your lab has adequate security precautions and it's all under lock and key at all times when you're not actively working on it. And they're farsighted enough that if you cannot order the DNA that could directly be used to make the virus, but you can order it in two pieces that any undergraduate student in biology could stitch together on their own and then have the illegal thing.

Tristan Harris: So you're saying if I right now say, hey, I want smallpox, I want to order it. Synthesis providers, they will not send me back smallpox if I order smallpox. But if I say, hey, I want half of smallpox but I don't call it smallpox, and this other half of smallpox and I don't call it smallpox, they will happily send me both those things.

Kevin Esvelt: I can't say that for sure with smallpox, but we did run a test recently with 1918 influenza. Now it's not a perfect test because we did place the order from a biosecurity org that doesn't do any wet lab research. So it has no reason to order DNA whatsoever. So we wanted to check how many of these companies would detect our orders and send us pieces of 1918 influenza virus. And it turns out that most of them did.

Daniel Barcay: That's really surprising to me that you can just split this up into two pieces. That feels like a pretty basic failure of security. Why does it exist like that? Why do you think that the security is so bad?

Kevin Esvelt: Well, there's two reasons. One, we don't always secure the right pathogens. So for example, there are some viruses that really should be on the select agent list, but that list was made with biological weapons for state actors in mind like anthrax, the stuff you can spray over a city and kill a bunch of people that way, not really geared towards pandemic viruses. So that's problem number one, we just didn't come up with the list right. But then the main one is they came up with the list when you couldn't make a virus from synthetic DNA, and so they've had to update the regulations over time to deal with advances in technology. And so it was honestly pretty impressive that they got as far as saying, "Yeah, you're not allowed to have the virus and you're not allowed to have the DNA encoding the virus either," but they didn't quite go as far as you're not allowed to have it in pieces.

Kevin Esvelt: And because of that, the synthesis providers are entirely within their rights. It is a hundred percent legal for them to ship you that DNA. If we required everyone to screen their orders to make sure you're not ordering something like 1918 pandemic influenza virus and check to make sure that people aren't ordering different pieces from different providers and ensure that the only people who can get that DNA have permission to work with the actual virus, then we would be a lot safer than we are now. And it wouldn't be very costly because the tools to detect these things exist. But here's where the AI comes in. Not now, but eventually we will be able to use AI tools to make variations on these existing viruses that won't have the same sequence but will have the same function. So that means our detection tools need to start detecting AI-designed biological weapons. And in fact, until the recent executive order on AI, there were no legal restrictions on DNA synthesis at all.

Tristan Harris: And just for listeners, President Biden's executive order on AI from last October did include restrictions on DNA synthesis for all labs that get government funding, but for all other labs, it just suggested a framework, nothing legally binding. But Kevin, there's a really basic and essential question we haven't actually asked yet. Why do researchers want to use AI tools to synthesize viruses in the first place?

Kevin Esvelt: Yeah, it's true that a number of bio-design tools are actually optimized for discovering new variants of viruses that are likely to cause pandemics. And you might say, what? Why would researchers ever do that? But there's an excellent reason why they want to do that. They want to design vaccines that will not just hit the current variant of the virus, they want to close off the paths to all the ones in the future, which means they need to predict how that virus is likely to evolve, and this helps them design the vaccine to prevent that. But the flip side is, you just made a tool that tells you how to change those sequences and not just one at a time, but together in a way that will escape all current immunity while still getting into ourselves.

Kevin Esvelt: In other words, once they're successful at this, and they're still getting there, they're not good enough yet, but if they're successful, then there will be this tool out there that we'll tell you how to make the next variant of COVID or influenza such that your version would spread and infect people throughout the world. So this is where access to those AI tools becomes an acute problem.

Tristan Harris: You're bringing up a few different things here that I want to lay out as separate distinct points of interest. So one is, AI is omni use. The same AI that can be used to optimize the supply chain can tell you where to break supply chains. The same AI that can tell you how to synthesize the vaccine can also tell you how to synthesize a million variations of the virus. And we always say we want to maximize the promise and minimize the peril. And I think an uncomfortable truth about AI is the promise is just the flip side of the peril.

Tristan Harris: And I'm thinking of the chemistry lab that was using AI and they said, "I wonder if we can use AI to find less toxic drug compounds." And the AI came back and it had found all these more healthy, safer versions of these drug compounds. But then they had the thought, "Well, I wonder if I could flip that around and say instead of finding less toxic compounds, I'm just literally going to flip one variable, say more toxic." They walked away from the computer, they came back six hours later and it had discovered 40,000 new toxic molecules including VX nerve gas. How do we deal with that? How do you reckon with that equation of the omniuseness of AI?

Kevin Esvelt: Well, I suppose if I had an answer to that, this would be the place to disclose. I guess I'm optimistic about AI because in a way I'm pessimistic about humanity. It does not seem to me possible to build a civilization in which every human alive could release a new pandemic whenever they want because some people would, whereas it seems quite possible to me that we could figure out how to ensure that every AI would never help them do that.

Tristan Harris: Could you then talk about the challenge of open-source AI? Because while the closed models from Anthropic, when you say, I'd like to build this biological weapon, please give me instructions how, and just to be clear for listeners, it'll say, no, I'm not going to do that. But the problem of open-source AI is if Meta trains their next Llama 3 model on a bunch of open biology data and biology textbooks and papers on a bunch of things in this area, and then they open up that model, whatever safety controls can be just stripped off because it's open source code. How do you think about the intersection of open-source AI models and this area of risk?

Kevin Esvelt: Right now it's not much of an issue in the sense that the models are not powerful enough to do a lot of harm. The thing about the LLMs, which are moving towards being general-purpose research assistants and perhaps eventually researchers themselves is that they'll be able to help people gain the skills of a human researcher. And for all the reasons we've discussed, human researchers today can make pandemic viruses. So the principle of defense first technology development just says, don't learn to make pandemics until you can defend. And defense is hard when the AI can keep making new variants that get around whatever vaccines you made. And it's a struggle to produce vaccines enough to protect everybody when someone malicious could just make a new pandemic. That suggests you need to move outside of biology for the defense. You need to prevent people from being infected in the first place. So all we need to do is invent protective equipment that will reliably keep us from getting infected with any pandemic virus, but we don't want to wear protective equipment moon suits all the time.

Tristan Harris: I was going to say a vision of the world where everyone is wearing a moon suit doesn't feel like a good stable state to land in.

Kevin Esvelt: No, definitely not. But imagine the lights in the room you're in don't just provide light that you can see to illuminate the area, they're also germicidal. They're emitting what we call far UVC light. And far UV light is effective at killing viruses and bacteria, but it's harmless to us. So we definitely would want this in public spaces, coffee houses, workplaces, stadiums, assembly halls, you name it. Maybe we want it in our homes, maybe we don't. But this is the kind of intervention along with just better ventilation in our homes in general that can just protect us from getting infected with anything, without having to wear clumsy protective equipment. There's lots of ways you might do this, but the goal is to just ensure that we never encounter biological information in a form that could get inside our bodies and hurt us, and this looks like a very solvable problem.

Tristan Harris: There's this sort of vision of like, okay, well we have AI times biology that lets us uncover all these amazing positive things, but in which basically a single person on any given day can hit a button, and then really horrible stuff is suddenly permeating the world. I would prefer to just not live in that world. I don't know if I would take the trade of all those benefits if the cost side of that equation is a world in which that's true. Even if those benefits were just literally the most seductive ever, it just feels kind of like a deal with the devil, where the other side isn't worth it. And I'm just curious to your reaction to that.

Kevin Esvelt: Well, given that I do run a biotechnology lab, I clearly think that biotechnology is a net positive for humanity. Even though I acknowledge that once we learn enough about how to program it, once we understand how it works, we by definition will be able to create new pandemics. I'm not saying we're anywhere close to that today, but I just don't see any way out of that dilemma. You acquire enough power, then you can rearrange the world. And you can use it for good or you can use it for ill. And I'm not sure that humanity, as we are today, is collectively responsible enough to deal with that level of power on an individual basis, which suggests you just don't let individuals have that. Don't let everyone order synthetic DNA. You can reduce the risk tremendously. But at the end of the day, the capability will be there if people can turn that information into atoms. And it looks to me like you can remove pretty much all the pandemic risk and keep all of the benefits. We just have to get serious about doing it.

Daniel Barcay: Let's talk about that. I am actually imagining there's just several big fixes. In the same way that we locked down photocopiers to make sure they're not printing $100 bills, we might be able to do very similar things and lock down the DNA synthesis providers, lock down a whole bunch of stuff, and end up in a world that's not perfectly safe, but more or less as safe as we are now, or more or less as safe as we were before genetic synthesis technology rolled out. Help me calibrate the level of risk, furthermore, the level of intervention that you think is necessary.

Kevin Esvelt: What you need to do is, yes, screen all the DNA that gets sent out as an order to a mail-in synthesis provider. You need to make sure that they're not going to just send it anyway even though it showed up as dangerous. That means you need to actually check them, make sure that they're licensed, make sure that folks try to get harmful DNA from them without authorization, and make sure that that doesn't happen.

Daniel Barcay: Is it something that takes a few million dollars in a year or is this something that is a massive society-wide project? How complex is this?

Kevin Esvelt: The former. There's less than a hundred DNA synthesis companies in the world, including those who make the DNA synthesizers themselves. There are more that sell short fragments of DNA, which eventually we'll need to screen, but still, you're talking a few hundred companies in the world. And there's multiple free screening systems that do a pretty darn good job of detecting hazards. And there's even ones that will turn the permissions that you have as a biologist. So my lab has permission to work with actually quite a number of different biological organisms, and there's software that can turn that list of organisms we can work with into what's called a public key infrastructure certificate.

Kevin Esvelt: So if you send that into a synthesis provider with your order, you could order any DNA from anything that you have permission to work with and it would just go through seamlessly. So we can basically automate away this whole problem by encoding the screening system into the DNA synthesis machines themselves. This would be really basic. Can you imagine a system where you're selling what could be the equivalent of enriched facile materials for nuclear weapons and you don't even check to see whether or not the person who ordered it has authorization?

Daniel Barcay: And so are there any barriers preventing this kind of fixes today? I mean, what's preventing us from being in the world where we just have good biosecurity?

Kevin Esvelt: Policymakers actually making it happen. One of the amazing things about the synthesis providers is that they recognized this was a problem and they got together and the biggest companies formed what's called the International Gene Synthesis Consortium. And they said, "Hey, we're all going to screen to make sure that we don't send nasty things." And they do their best, and they do this at cost to themselves. Because when someone orders a hazard, they then need to decide should we send it or should we not send it, which takes time, and time is money. But they do this because it's the right thing to do, which is a rare example of people acting against their incentives to do the right thing. But the problem is there's only so far they can go. These technologies already exist, we just need people to use them. In order to get people to use them, governments need to require them.

Kevin Esvelt: Because the IGSC does their best, but if they're too much of a pain to customers who for good scientific reasons order hazards, those customers are going to place the order from a company that doesn't give them as much of a hassle. So it's just a problem for governments, and that means we need action from multiple governments, particularly the US, China, and EU, which are far and away the largest markets. Virtually all DNA synthesis providers and manufacturers are in one of those countries or 90% of their business is to one of those three markets. If they just all get together and require this, which again costs almost nothing, then we have mostly solved this problem.

Daniel Barcay: I mean that's so exciting. I have to admit that usually, it's CHT, we end up depressing people. We bring them into a problem and we say, "No, no, no, it's so much more complicated than you imagine. There's so many more bad incentives than you imagine." But I have to admit, I'm actually kind of cheered up by this call because in the end of the day, actually this could be solved for the low millions of dollars, it's just we need to act now. We need to change the incentives, change the regulation, and get the protection in place. But from what you're saying, this is actually a solvable problem and this is a problem we should actually just lock down.

Kevin Esvelt: Yeah. We could make DNA as secure as enriched facile materials that we locked down because otherwise they could be used to build nuclear weapons. This is totally achievable.

Daniel Barcay: Someone in your position, I imagine one of the difficult things is some of the risks that you're looking at, you both want public awareness for because you want to patch these holes, you want to spend the tens of millions of dollars, recall all the synthesis machines and install these protections. And at the same time, you don't want to shout from the rooftops how vulnerable we are. Can you talk a little bit about that tension and what you see the sort of information risks are?

Kevin Esvelt: You've just clearly articulated the basic horror and burden of my life, which is: If you think you see a way to cause catastrophic harm, how do you prevent it without articulating it and making it more likely? Which is why I'm very careful with my words. I'm not saying that we're at risk of a pandemic right now. That would be deliberate because there's detailed instructions. What I will tell you is that I'm concerned about 1918 influenza because there is probably a... I don't know, maybe a 10% chance if you ask a bunch of virologists that it might actually cause a pandemic today. And it would probably be COVID level, it wouldn't be nearly as bad as in 1918 because a lot of us have immunity. To me, a 10% chance is enough to get people concerned about it. But if you're a bioterrorist, are you really going to go all of this trouble for a 10% chance? Seems pretty unlikely.

Kevin Esvelt: Now, I could be wrong about that calculation. Maybe we'll roll the dice and 10-sided die comes up a one. That's always possible. But if we don't lay out some concrete scenario of something that could go wrong, I've found nothing happens. And you can't just talk to policymakers behind closed doors either. You have to lay out something there for people to talk about and think about and understand where we're going in order to build momentum to get something to happen. I find it incredibly striking that the only effective governmental action we have on getting DNA synthesis screening in place came with the executive order on AI because people were concerned enough about AI eventually creating bio risk that we put that in there to close off these bits to atoms transition as we should have.

Tristan Harris: Do you feel confident in the executive order, which is not fully legally binding in the way that it will shift towards more of these solutions and policy, or do we need a lot more action from Congress?

Kevin Esvelt: We need action from Congress. The executive order only covers institutions that take federal money. So if you take federal money or your institution does, then you're supposed to buy DNA from a company that will attest that they screen their orders. And there will be audits, red teams, that check to see. I can't guarantee that they're going to be robust by my standards, but they're supposed to be there. But still, is there going to be any kind of stick forcing companies that say they screen to actually up the standard? I don't know. It's very unclear.

Kevin Esvelt: But if you have a startup or you're not accepting federal funds for whatever reason, it doesn't apply to you. You can buy DNA from whoever you want. What's more, it doesn't apply to the providers at all. So we need action from Congress to close that loophole. And while they're at it, they could fix the Select Agent Program loophole as well, where it's fine if you buy the DNA in two pieces, as soon as you put it together, it becomes illegal. Just fix that one and improve the executive order a little bit, get that in law and we'll be off for the races and I can sleep better at night.

Tristan Harris: So Kevin, about a year ago, the CEO of Anthropic Dario Amodei testified before Congress about AI risk, and he talked about this exact issue.

Dario Amodei: A straightforward extrapolation of today's systems to those we expect to see in two to three years suggests a substantial risk that AI systems will be able to fill in all the missing pieces, enabling many more actors to carry out large-scale biological attacks. We believe this represents a grave threat to US national security.

Tristan Harris: So a lot of people hear this and they think that Anthropic is just trying to scare people and hype up these dangers that the US government will regulate AI, stop open source, and then only Anthropic, OpenAI, and Google will be able to sort of be stewards of this AI future. What do you think of that? Is this a regulatory ploy? Do you agree with Dario's timeline that he gives here?

Kevin Esvelt: I definitely do not think that it is a regulatory ploy. I believe it is sincere. My concern is that we will fail to take action because we believe it is unlikely that these capabilities will exist within three years. I don't like giving timelines because it's so hard to anticipate capabilities. And I do feel that at least in bio-design tools, we are very data-limited right now for most things. But even conceptually it seems plausible. That means we do need to evaluate capabilities on newly trained models before they're released. This can mostly be done by working with the industry leaders. We do need some kind of policy framework with teeth to ensure that those systems are not rolled out and made available in a form that can still be jailbroken if we truly do believe that they can describe ways of causing harm much worse than COVID, much worse than 1918 influenza, as bad as smallpox or even worse.

Tristan Harris: It seems like there's this tension where as we do science, we start off in an open way. We publish all the papers, we publish our discoveries. We are doing quantum physics in 1930s, and we publish everything we're doing. And then at some point, some people realize, "Oh shoot, there's some really dangerous things you could do," and we stop publishing. And that's happened a little bit in AI. And I'm just curious to ask you about what should happen with biology going from this open approach to do we need to go to a slightly more closed model?

Kevin Esvelt: I'm actually going to push back on your framing because I think we're not nearly as open in science as we could be, indeed as we should be. We don't disclose our best ideas until we've largely realized them ourselves and can tell the story ourselves in order to get all the credit. I'd love to change the incentives to disclose our best ideas early so that we can better coordinate how to realize them. I very strongly default to total transparency. It's just that I also recognize that there is at some point a capability that if misused could be destructive enough that it's not worth the risk anymore. And I think it flips about the time when you can cause a COVID-level pandemic.

Kevin Esvelt: And I'm tremendously sympathetic to the position of the folks that say, "Look, this just seems like a power play. We're really worried about the centralization of power." Well, I am too, but I'm also worried about too much power in the hands of individuals who might be mentally unstable or captured by a horrific ideology. So the way that we deal with those people is we structure society so they can't do very much harm, and we impose checks and balances on government so that no central power source can do that much harm.

Tristan Harris: Kevin, I think it's been an incredibly sobering conversation about some real risks. I just want to thank you for all of the incredible work that you do, and there's a number of solutions that you've outlined from far UVC light to metagenomic testing and secure DNA screening. There's a number of things that policymakers, if they took this conversation seriously, could do. And I just want people to focus on that and get the work done. And thank you so much for coming on Your Undivided Attention.

Kevin Esvelt: Thank you so much for everything that you're doing to mitigate not just this risk but all of the different ways that the shining source of our greatest hopes could be turned against us. Deeply grateful. Thank you.

Clarification: President Biden’s executive order on DNA synthesis only applies to labs that receive funding from the federal government, not state governments.

![[ Center for Humane Technology ]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!uhgK!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5f9f5ef8-865a-4eb3-b23e-c8dfdc8401d2_518x518.png)