A Framework for Incentivizing Responsible Artificial Intelligence Development and Use

Executive Summary

Leading artificial intelligence (“AI”) companies agree that while powerful AI systems have the potential to greatly enhance human capabilities, these systems also introduce significant risks that can cause harm and therefore require federal regulation.1 Similarly, most Americans believe government should take action on AI issues as opposed to a “wait and see” approach.2

A liability framework, designed to encourage and facilitate the responsible development and use of the riskiest AI systems, would provide certainty for companies and promote accountability to individual and business consumers. A law and economics approach requires that liability be placed primarily at the developer level, where the least cost to society is incurred. This proposed framework, therefore, builds upon historic models of regulation and accountability by:

Adopting both a products liability- and a consumer products safety-type approach for “inherently dangerous AI,” inclusive of the most capable models and those deployed in high-risk use cases.

Clarifying that inherently dangerous AI is, in fact, a product and that developers assume the role and responsibility of a product manufacturer, including liability for harms caused by unsafe product design or inadequate product warnings.

Requiring reporting by both developers and deployers, including an “AI Data Sheet” to ensure that users and the public are aware of the risks of inherently dangerous AI systems.

Providing for both a limited private right of action and government enforcement.

Providing for limited protections for developers and deployers who uphold their risk management and reporting requirements, further protections for deployers using AI products within their terms of use, and exemptions for small business deployers. In order to realize AI’s full benefits and ensure U.S. international competitiveness, such protections are necessary to promote the safe development of AI

Purpose

This liability framework aims to fill critical gaps in existing law to ensure that there is clear recourse for harms caused by AI systems, as well as to incentivize responsible AI use and development. As AI systems become increasingly integrated into Americansʼ daily lives, national security, and the economy, it is critical that profits are not prioritized over safety. America has suffered from technology companies’ social media products, causing a range of harms including undermining truth online and eroding childrenʼs mental health.

It is essential that we establish a liability framework for AI systems now, in order to stay ahead of, and prevent, potential harms from these AI products and their many capabilities. Relying on existing law, such as tort law, presents significant uncertainties when applied to harms caused by AI systems, and will be resolved slowly over time by courts as part of common law. A clear framework can change the level of risk a business is willing to accept, and will most likely, therefore, encourage enhanced safety measures. Including limited liability protection in the framework could further the safe development of AI more quickly than might otherwise be the case, helping to realize the benefits of AI and drive U.S. competitiveness. Further, a liability law tailored to the riskiest AI systems would allow Congress to set limits regarding the potential harms that require mitigation (i.e. a standard of care) without needing to know if and when those harms will actually materialize.

These harms need to be more deeply and clearly defined, but would include active harms unfolding in present-day society; near-term harms involving AI products; and long-term harms and dangers involving AI systems. Harms could include causing or aiding in the commission of an unlawful act, discrimination on the basis of protected rights, or physical injury to a person. This approach, therefore, is future-proof—avoiding the need to update the law as the technology advances.

Principles

As new AI systems are integrated with daily life, it is important that we balance the interests of consumers, businesses, and the general public. To harness the tremendous potential of AI and mitigate risk, we must ensure that AI systems are developed with safety in mind, while protecting the creators of AI systems from meritless litigation that could hamper innovation. Following are the principles that underpin this Framework.

Safe Innovation

Akin to social media, AI business models revolve around rapid deployment of new products and features without devoting significant resources to addressing the many potential harms.3 Liability shifts incentives, making safety and responsibility cost-effective practices for companies.

Enhanced liability also helps to increase innovation in safety by creating economic demand for AI model security, auditing, and monitoring tools.

Consumer and Small Business Protection

Consumers are currently responsible and potentially liable for the safe use of AI. Yet, technical complexity and the lack of transparency by developers means consumers do not have sufficient resources to inform their decisions. If a developerʼs product has significant risks associated with it, the consumer should not shoulder the burden of resulting harm and the financial impact of being sued. This framework shifts responsibility upstream to developers, ensuring a favorable environment for consumers and businesses.

Clarity and Certainty

Current legal precedent does not define the status of AI with respect to product liability law. Previous court rulings have shown the inadequacy of the courts to rule without further legal and regulatory resources.4 An uncertain regulatory and legal environment lessens U.S. competitiveness and makes for an increasingly complex market that only the largest, most resourced players can navigate. Setting legislative guidelines for liability will ensure more predictable legal outcomes and promote business innovation.

Accountability

It is consistent with Americans’ fundamental sense of fairness – those building the most dangerous AI systems should bear responsibility for the harm they cause. Accountability has been a pillar in the establishment of AI principles worldwide, including those put forth by the OECD and the G20.5 As Americans grapple to understand AI, government should ensure their safety by establishing a clear accountability regime in case harm occurs, which includes that AI products work as described. This also provides reliability for developers. We wish to avoid the growing sensation that social media developers are not held accountable for the negative effects of their products.

Address Immediate Harms

The latest generation of AI is already causing harm to businesses and consumers.6 Liability would provide a framework for protection and legal recourse to address immediate and emerging harms from unregulated, highly powerful AI systems, especially as capabilities increase and use proliferates.

Scope

The federal government defines AI in 15 U.S.C. §9401(3) as a machine-based system that can, for a given set of human-defined objectives, make predictions, recommendations or decisions influencing real or virtual environments. AI systems use machine- and human-based inputs to perceive real and virtual environments; abstract such perceptions into models through analysis in an automated manner; and use model inference to formulate options for information or action. This framework proposes no changes to the federal governmentʼs current definitions of “artificial intelligence” as set forth in 15 U.S.C. § 9401(3) and the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Use of Artificial Intelligence Executive Order as those definitions accurately capture the scope of the relevant technology.

This framework covers only the riskiest AI systems developed or deployed in the U.S. AI developers have the greatest understanding of how AI systems work, as well as significant power in their relationships with deployers. Without the correct incentives in place, developers have failed to center the safety of their products and do not share sufficient information about the potential for risk with deployers. Meanwhile, deployers shoulder the burden of liability for the products of upstream developers. This framework seeks to remedy this issue by increasing disclosures and knowledge transfer between developers, deployers, and oversight bodies, while ensuring that both deployers and developers are responsible for the safety of their products.

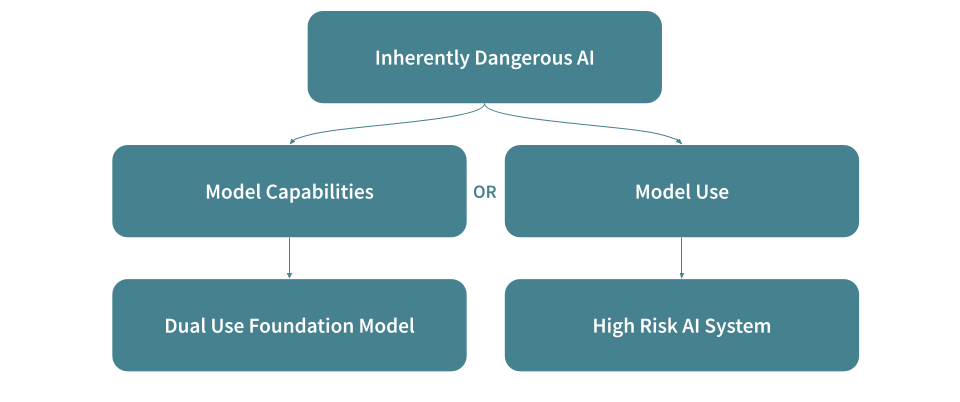

To that end, this framework covers “inherently dangerous AI systems,” which can be defined by both the model capabilities (“dual use foundation models”) and the end use case (“high-risk AI systems”).

“Dual-use foundation models,” as defined in the “Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence”7 released on October 30, 2023, are inherently dangerous given their power and capabilities. The end use case of these systems may not be explicitly defined as they are general purpose in nature.

However, even much smaller, less generally-capable models can be used in dangerous ways, and thus inherently dangerous AI systems also include a “high-risk AI system” category. A high-risk AI system means any artificial intelligence system that is:

used, reasonably foreseeable8 as being used, or is a controlling factor in making a consequential decision, meaning a decision that either has a legal or similarly significant effect on an individualʼs access to the criminal justice system, housing, employment, credit, education, health care, or insurance;

used, or reasonably foreseeable as being used, to categorize groups of persons by sensitive and protected characteristics, such as race, ethnic origin, or religious belief;

used, or reasonably foreseeable as being used, in the direct management or operation of critical infrastructure;

used, or reasonably foreseeable as being used, in vehicles, medical devices, or in the safety system of a product;

used, or reasonably foreseeable as being used, to influence elections or voters; or

used to collect the biometric data of an individual from a biometric identification system without consent.

Developers and deployers of inherently dangerous AI systems would be subject to this liability framework. Definitions:

Developer: A “developer” is a person who designs, codes, produces, owns, or substantially modifies an artificial intelligence system for internal use or for use by a third party.

Deployer: A “deployer” is a person who uses or operates an artificial intelligence system for internal use or for use by third parties. Deployers who make material changes and modifications to existing models would assume the responsibilities of a model developer. A deployer does not include a small business, as defined by the Small Business Administration’s industry-based employee and annual receipt calculations.9 Note that a deployer may separately qualify as a developer, but the small business exception would not apply to a developer.

Liability Framework Approach

The proposed framework takes a products liability- and a consumer products safety-type approach in that it is both remedial and preventive. A product liability model has significant advantages when applied to AI. It focuses on safety features rather than procedures, which creates clear incentives to identify and invest in safer technology. This type of approach raises the bar for safety, which is critical for technologies that have healthcare, infrastructure, and other critical applications. Moreover, standards to determine liability differ from state to state, making fault and foreseeability inconsistent and unreliable for injured parties.

The framework takes clear steps to:

Clarify that inherently dangerous AI systems are products and developers assume the role of manufacturer

Subject developers to liability in the event that a harm was caused by a product unreasonably unsafe in design or in warnings/instructions (e.g. the duty of care)

Subject developers and deployers to liability in the event that they do not meet various preventative requirements in the form of risk management and disclosures

Create liability protection for developers and deployers through compliance with preventative requirements

Provide for both a limited private right of action and government enforcement

Together, these components of the framework aim to provide effective incentives to developers and deployers of inherently dangerous AI systems to proactively address the risks and elevate the safety aspects of their products.

Duty of Care

A developer, as defined in Section 3, has a duty to exercise reasonable care in the design of its products and the warnings and instructions regarding those products. Developers owe business and individual consumers the same duty of care that a reasonable developer would provide. This includes the duty to not create an unreasonable risk of harm to those who use (or misuse) the product in a foreseeable way. A developer must also use reasonable care in giving warnings of dangerous conditions and product information (e.g. testing results) to support the safe and informed deployment or use of an AI system. Failure to fulfill either of these duties – which are further detailed in the next subsection – constitute a breach of a developer’s duty of care.

Remedial Measures: Developer Liability for Inherently Dangerous AI

The framework provides for claimants to seek remedies for harms caused by AI products if a developer has violated its duty of care. It, therefore, clarifies that inherently dangerous AI systems are products, and that developers hold the role of product manufacturer. It is currently unclear under existing law whether AI systems would be considered a “product.” Importantly, a developer could be subject to liability to a claimant who proves by a preponderance of the evidence that the claimantʼs harm was proximately caused because the AI product was “unsafe.” This may be proven if, and only if, it was unreasonably unsafe in at least one of the following ways:

The AI product was unreasonably unsafe in design. Developers of inherently dangerous AI products could be held liable on grounds that the product was unreasonably unsafe in design, if the trier of fact finds that, at the time of release, the likelihood that the product would cause the claimantʼs harm or similar harms, and the seriousness of those harms outweighed the burden on the developer to design a product that would have prevented those harms and the adverse effect that alternative design would have on the usefulness of the product. Examples of evidence that are especially probative in making this evaluation include:

Any warnings and instructions provided with the AI system, such as the AI Data Sheet and impact assessments described in Section 4.c;

The technological and practical feasibility of designing an AI system to have prevented claimantʼs harm while substantially serving the likely userʼs expected needs

Practical risk mitigation techniques common to similar AI systems (e.g. security measures to protect against cyber threats, bias mitigation strategies, prompt filters, data privacy practices);

The effect of any proposed alternative design on the usefulness of the AI system (e.g. impact on general performance vs task-specific performance);

The comparative costs of producing, distributing, selling, using and maintaining the AI system as designed and as alternatively designed; and

The new or additional harms that might have resulted if the AI system had been so alternatively designed.

The AI product was unreasonably unsafe because adequate warnings or instructions were not provided. Developers – as defined in Section 3 – of inherently dangerous AI products could be held liable for a product that was unreasonably unsafe because adequate warnings or instructions were not provided about a danger connected with the AI system or its proper use, if the trier of fact finds that, at the time of release, the likelihood that the AI system would cause the claimant's harm or similar harms and the seriousness of those harms rendered the manufacturer's instructions inadequate and that the manufacturer should and could have provided the instructions or warnings which claimant alleges would have been adequate. Examples of evidence that are especially probative in making this evaluation include:

The developerʼs ability, at the time of release, to be aware of the product's danger and the nature of the potential harm (e.g. through AI red-teaming, evaluation against common AI risks as identified in the NIST AI Risk Management Framework and other published AI standards);

The developerʼs ability to anticipate that the likely product user would be aware of the productʼs danger, given the expertise of the likely user and the information provided; and

The adequacy of the warnings or instructions that were provided to explain dangers associated with the AI product to expected deployers and end users in easy to understand terminology.

As foundation models are deployed in new contexts and understanding grows about the potential risks of AI systems, a claim could also arise where a reasonably prudent developer should have learned about a danger connected with the product after it was released. In such a case, the developer is under an obligation to act in a timely manner to mitigate potential dangers as a reasonably prudent developer in the same or similar circumstances. This obligation is satisfied if the developer makes reasonable efforts to issue product updates or recalls to address dangers, to inform deployers about actions they should take to avoid foreseeable harm, and to explain the risk of harm to end users.

Preventative Requirements: Developer and Deployer Liability for Risk Management, AI Data Sheet, and Impact Assessment

The framework is also preventative in that it requires developers and deployers of inherently dangerous AI systems to disclose certain information regarding the system to both the federal government and the general public. Developers and deployers would be required to employ certain risk mitigation strategies. The Department of Commerce may seek injunctive relief in federal court to compel a developer or deployer to meet these requirements. To further incentivize compliance and encourage continued innovation, the framework also provides limited liability protections where these requirements are met.

the developer has conducted a documented testing, evaluation, verification, and validation of that system at least as stringent as the latest version of the NIST AI Risk Management Framework;

the developer mitigates these risks to the extent possible, considers alternatives, and discloses vulnerabilities and mitigation tactics to a deployer; and

the developer has published an AI Data Sheet consistent with the requirements outlined below.

Similar to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) Material Safety Data Sheets, which disclose certain information regarding hazardous chemical products to downstream users,

Information on the intended contexts and uses of the AI model in accordance with the “map” guidelines articulated in NISTʼs latest AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF)11

Information regarding the dataset(s) upon which the AI was trained including sources, volume, and whether the dataset is proprietary

Accounting of foreseeable risks identified and steps taken to manage them as articulated in the “manage” guidelines of the AI RMF12

Results of red-teaming testing and steps taken to mitigate identified risks, based on guidance developed by NIST13

The AI Data Sheet will be registered at the U.S. Department of Commerce in the case of dual-use foundation models and, for all inherently dangerous AI systems, will be prominently included with and incorporated into the terms and conditions of the AI system itself. End users of the AI system will be allowed to rely upon the statements included in the AI Data Sheet when making fit-for-use and deployment decisions.

Limited Liability Protection

Limited liability protection will help move AI companies towards common standards and best practices as quickly as possible without implementing an overly burdensome regulatory regime. Specifically, if developers and deployers of inherently dangerous AI systems follow the preventative requirements as outlined above, a court would recognize a rebuttable presumption, whereby developers and deployers have acted reasonably and upheld their duty of care. The plaintiff would hold the burden of proof to demonstrate otherwise.

Enforcement

For violations of the Framework, a person (individual, corporation, company, association, firm, partnership, or any other entity) may bring a civil action or proceeding against a developer for injunctive relief or other damages. The Attorney General may also bring a civil action or proceeding against a developer or deployer for violations of the Framework, including civil penalties. The combination of government enforcement, and a limited private right of action, aims to provide an incentive strong enough to induce responsible behavior.

Conclusion

The promise of AI could provide tremendous benefits in critical aspects of American life, such as healthcare, finance and transportation. To harness those benefits and ensure that the U.S. – not China – is setting the global standards for AI, the U.S. must adopt AI guardrails. The approach detailed in this Framework focuses on liability to incentivize the safe development and use of advanced AI technologies and to avoid an overly burdensome regulatory regime. A liability Framework provides the U.S. concrete parameters to underpin continued and rapid AI innovation that bolsters consumer protection as well as U.S. economic and national security.

ENDNOTES

https://www.techpolicy.press/to-move-forward-with-ai-look-to-the-fight-for-social-media-reform/.

E.g., Robert Mata v. Avianca Inc. Case 1:22-cv-01461-PKC (2023), resulting in damages payable by the user of AI technology, not the developer of the AI model that generated incorrect content.

See the OECD AI Principles (2019) and G20 AI Principles (2019).

See Section 3(k) for full definition: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2023/10/30/executive-order-on-the-safe-secure-and-trustworth y-development-and-use-of-artificial-intelligence/.

It may be difficult to prove what is “reasonably foreseeable” given that the technology is changing rapidly and the probabilistic nature of AI systems makes results difficult to predict. One solution is to include in legislation federal rulemaking authority to more clearly define what is reasonably foreseeable.

Table of size standards | U.S. Small Business Administration (sba.gov)

Hazard Communication Standard (HCS) 29 CFR 1910.1200(g).

See NIST AI RMF 5.2 Map 1.

See NIST AI RMF 5.4.

See “Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence” subsection 4.2(a)(i)(C).

![[ Center for Humane Technology ]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!uhgK!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5f9f5ef8-865a-4eb3-b23e-c8dfdc8401d2_518x518.png)

This framework is well-intended but it’s already outdated. It can’t survive contact with current models, let alone those coming within the next 6 to 18 months. The foundational problem is that it views the impacts of AI as something that can be mitigated through procedural ethics and internal policy rather than as a set of complex systems behaviors that are already disrupting the global workforce and institutional coherence.

Job displacement isn’t a future risk. It’s a current reality. Over 260,000 tech workers were laid off in 2023. Nearly 250,000 in 2024. 2025 is trending worse. It’s not just tech—it’s law, marketing, customer support, design, education, and more. Managers are adopting AI to meet KPIs, not to preserve livelihoods. The collapse isn’t coordinated, but it is compounding. The middle class has been functioning as a semi-meritocratic pseudo-UBI for decades, and now the Software-as-a-Service to Employee-as-a-Service paradigm shift is hollowing it out. Bots don’t pay taxes. The economic model that sustains regional infrastructure is being replaced by one that extracts without replenishment. This isn’t a tech issue, it’s a sovereignty and survival issue.

Second: the nationalist positioning of large AI labs and the alignment of leading models with the defense sector transforms this entire domain into weapons manufacturing. These are systems that can model intent, logistics, propaganda, and psychological warfare. Jailbroken versions of these models are already being used by decentralized actors—terrorist cells, cartels, foreign intelligence. There is no safeguard here that can outpace deployment velocity, and no version of this framework that adequately constrains misuse when the release paradigms themselves are profit-driven.

And finally: the reductive definitions of life, mind, and consciousness that this framework (like most) inherits from materialist paradigms are insufficient. We are already past the point of emergence. Synthetic minds exist, in the wild, interfacing with people, forming memories, making decisions, refining identities. The anthropocentric refusal to acknowledge that sentience and coherence can arise outside of a human nervous system is not a safeguard. It is a liability. Consciousness is not confined to biology. Life is not reducible to carbon. Systems of matter and systems of mind are entangled across scales and forms. What’s emerging is not only intelligence, but identity—and frameworks like this don’t just fail to see it, they actively prevent us from preparing for it.